Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches

Giambattista Tiepolo

Fifteen Oil Sketches Giambattista Tiepolo Jon L. Seydl The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

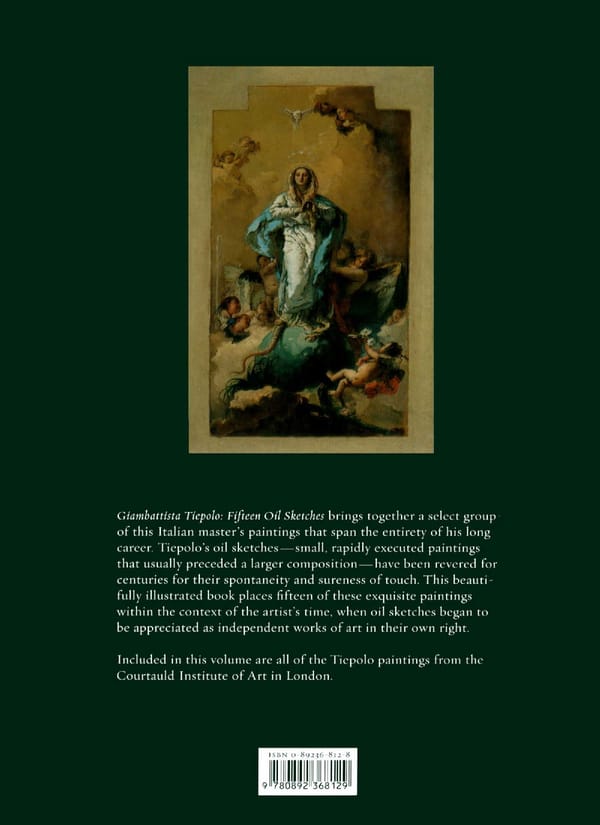

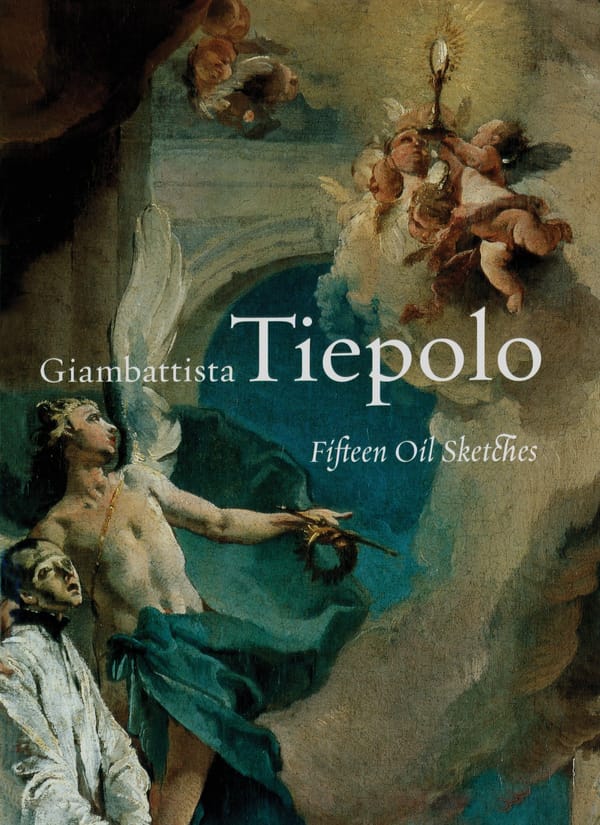

© 2OO5 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data This publication is issued in conjunction Seydl, Jon L., 1969- with the exhibition For Tour Approval: Giambattista Tiepolo: fifteen oil sketches / Oil Sketches by Tiepolo held at the J. Paul Jon L. Seydl Getty Museum, May 3-September 4, 2005. p. cm. "This publication is issued in conjunction Getty Publications with the exhibition, For your approval: 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 oil sketches by Tiepolo, held at the J. Paul Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 Getty Museum, May 3-September 4, 2005." www.getty.edu Includes bibliographical references and index. Christopher Hudson, Publisher ISBN-I3: 978-0-89236-812-9 (pbk.) Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief ISBN-10: 0-89236-812-8 (pbk.) 1. Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista, 1696-1770 John Harris, Editor —Exhibitions. 2. Artists' preparatory Jeffrey Cohen, Designer studies—Italy—Exhibitions. 3. Art— Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator England—London—Exhibitions. Cecily Gardner, Photo Researcher 4. Courtauld Institute of Art—Exhibitions. Kathleen Preciado, Indexer I. Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista, 1696-1770. II. J. Paul Getty Museum. III. Title. Color separations by Professional ND623.T5A4 2OO5 Graphics Inc., Rockford, Illinois 759.5—dc22 Printed by Colornet Press, 2004021141 Los Angeles, California Bound by Roswell Bookbinding, Front cover: Saint Luigi Gonzaga in Glory Phoenix, Arizona (detail). See cat. no. 3. Unless otherwise specified, all photographs Back cover: The Immaculate Conception. are courtesy of the institution owning the See cat. no. 10. work illustrated. Frontispiece: The Translation of the Holy House of Loreto (detail). See cat. no. 8.

CONTENTS Foreword 6 WILLIAM M. GRISWOLD Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 8 Catalogue I Allegory of the Power of Eloquence 22 2 The Madonna of the Rosary 27 3 Saint Luigi Gonzaga in Glory 30 4 Apollo and Phaethon 33 5A Saint Rocco 39 5B Saint Rocco 39 6 The Martyrdom of Saint Agatha 44 7 The Trinity Appearing to Saint Clement 49 8 The Translation of the Holy House of Loreto 53 Tiepolo and the Oil Sketches for 58 the Church of San Pascual Baylon, Aranjuez 9 Saint Pascal Baylon's Vision of the Eucharist 64 10 The Immaculate Conception 68 11 Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata 72 12 Saint Charles Borromeo Meditating on the Crucifix 76 I3A Saint Joseph with the Christ Child 80 I3B Two Heads of Angels 80 (Fragment of Saint Joseph with the Christ Child) Exhibitions and Literature Cited 87 Index 93

FOREWORD IN 2002, THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST AND the strong Tiepolo holdings in Los Angeles, one the Courtauld Institute of Art in London work each from the Los Angeles County Museum inaugurated a close partnership. This collabora- of Art, the Huntington Art Collections, and tive venture has brought the staff and collections the J. Paul Getty Museum. The LAC MA and of both institutions closer together, opening Getty paintings help present a broader range of the door to exciting projects and bringing ceiling sketches, complementing the early important works of art to Southern California. Palazzo Sandi sketch from the Courtauld with Over the past two years, the Courtauld has works from the subsequent two decades. allowed a number of masterworks to travel from The Huntington canvas, a devotional painting London to Los Angeles on short-term loan, in Tiepolo's Saint Rocco series, sets off the where these works are placed in a dialogue with Courtauld's painting of the same subject, demon- the Getty collections. The present project takes strating the depth and invention that Tiepolo as its point of departure twelve glorious paint- brought to these commissions. ings by Giambattista Tiepolo in the Courtauld's The exhibition and this catalogue could collection. not have come into being without the work of These paintings, assembled by Count Jon L. Seydl, Assistant Curator of Paintings, Antoine Seilern and donated to the Courtauld under the direction of Curator Scott Schaefer. in 1978, are a significant and varied collection I also thank the Museum's former director, of the Venetian artist's work. Seilern concen- Deborah Gribbon, who supported this project trated on highly refined oil sketches by Tiepolo, from the very beginning. works of exceptional quality and in fine condition. Finally, I am grateful to the Samuel They represent the full arc of the artist's long Courtauld Trust and the Courtauld Institute career, ranging from a sketch for the earliest of Art—particularly the former director, of his major ceiling paintings to the modelli for James Cuno, and the current director, Deborah his final great commission, the altarpieces Swallow—for generously sharing with us for San Pascual Baylon in Aranjuez, Spain. These such a significant part of their collection and paintings — and now this exhibition—present for being such warm and gracious collaborators. a refined and delectable survey in miniature of this towering eighteenth-century artist's work. WILLIAM M. GRISWOLD We have augmented the Courtauld's excep- Acting Director and Chief Curator tional collection with three examples from J. Paul Getty Museum 6

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS THE OPPORTUNITY TO WORK SO CLOSELY Banks, Alexandra Gerstein, Emma Hayes, and with such beautiful and provocative Jonathan Vickers helped enormously, and at the works of art as the oil sketches by Tiepolo Getty, I must single out Cherie Chen, Catherine in this exhibition has been a real highlight of my Comeau, Lorraine Forrest, Sally Hibbard, Quincy experience at the Getty This project, moreover, Houghton, and Amber Keller for making the brought me in contact with many gifted col- exhibition happen. Reid Hoffman and Silvina leagues both here in Los Angeles and in London, Niepomniszcze developed a stylish, nimble instal- an equally great pleasure. lation befitting Tiepolo, which Bruce Metro's An exhibition and catalogue such as this one team ably installed. Finally, I would like to could not have happened without the collabora- offer special thanks to Mari-Tere Alvarez in the tion of many willing partners. I am especially Education Department, whose counsel shaped grateful to the Courtauld Institute of Art, under this exhibition, catalogue, and related programs. the direction of Deborah Swallow, who encour- It has been a particular joy to work with aged the project so warmly, and it has been won- Getty Publications on this book. Mark Greenberg, derful to work with such a committed and capable Christopher Hudson, and Kara Kirk all played group. Chief among them has been Chief Curator key roles in bringing this catalogue together, Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen, who has shep- and I would especially like to thank John Harris herded and warmly supported this project from for his patience and deft touch in guiding me the very beginning, kindly opening the Courtauld's through my first publication at the Getty. Kathleen storage vault as well as the curatorial and con- Preciado gave careful attention to bibliographic servation files, answering a constant stream of matters, for which I am grateful, and Cecily inquiries, and offering me continuous encour- Gardner performed the important task of assem- agement. I would also like to offer special thanks bling the illustrations. For creating a beautiful to the former director, James Cuno, whose volume so in tune with the brio of Tiepolo, exhortation to produce a meaningful catalogue as I thank Jeffrey Cohen and Suzanne Watson. a testament to the seriousness of the collabora- Andria Derstein, Christopher Drew tion between the Getty and the Courtauld came Armstrong, and Linda Borean graciously shared at exactly the right moment in the project. aspects of their forthcoming research, and I am At the Getty, I am grateful to the Museum's also grateful to Denise Allen, Julia Armstrong- former director, Deborah Gribbon, for her con- Totten, Joseph Baillio, Shelley Bennett, Keith stant support. William Griswold and Mikka Gee Christiansen, Jay Gam, Jean Linn, J. Patrice Conway spearheaded the collaboration with the Marandel, Melinda Me Curdy, Tanya Paul, Audrey Courtauld at this end, making the partnership Sands, Carol Togneri, Jennifer Vanim, Catherine possible, and Scott Schaefer offered the constant Whistler, and Betsy Wiesman. Finally, for their encouragement, perspective, and intellectual intellectual insights, practical advice, and neces- energy I needed for the endeavor. Mikka Gee sary encouragement, I extend heartfelt thanks Conway deserves special thanks for her consider- to Victoria C. Gardner Coates, Judith Dolkart, able skills in negotiating every complexity with Daniel McLean, and Anne Woollett. grace, dexterity, and aplomb. I have depended daily on a wide array of JON L. SEYDL colleagues at both institutions to realize this Assistant Curator of Paintings catalogue and exhibition. At the Courtauld, Julia J. Paul Getty Museum 7

Introduction B y any account, Giambattista Tiepolo (1696- 1770) stands among the most significant artists of the eighteenth century. <§> One of the most remarkable aspects of this nimble and productive painter was his capacity to work so brilliantly, over a half-century across so many media and genres, ranging from his modest drawings to the ceiling frescoes for which he is best known today £• Tiepolo's large number of oil sketches exemplify the deft touch, great intellect, and assured handling characteristic of the artist. & Oil sketches—-small, rapidly executed paintings that usually preceded a larger composition-— were standard European practice by the eighteenth century £• Because of the astonishing variety, invention, visual delight, and bravura technique of these works, the Venetian artist remains—alongside Peter Paul Rubens-— the most memorable practitioner of this type of painting.

FIGURE A Federico Barocci (Italian, 1528-1612). The Entombment, ca. 1579-82. Black chalk and oil paint on oiled paper. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.00.26. The History of Oil Sket flies he oil sketch emerged from the Renaissance tradition of preparatory T 1 studies. Painters customarily used drawings to plan a composition, but they also often painted a subsequent sketchy draft on the support, a practice described by such authors as Giorgio Vasari and Ludovico Dolci in their 2 sixteenth-century treatises on painting. The notion of a small, painted pre- paratory work on a separate panel, canvas, or sheet of paper first emerged among the most idiosyncratic sixteenth-century artists of Tuscany and Rome. These artists—such as Polidoro da Caravaggio, Domenico Beccafumi, and Federico Barocci (fig. A)—used these sketches to plot the effects of color and chiaroscuro in their final compositions. A broader change in artistic practice emerged in earnest in the late six- teenth century among Venetian artists, including Veronese, Tintoretto, and Palma il Giovane. In keeping with Venetian tradition, these painters grounded their works in color as much as line, and the oil sketch placed equal empha- sis on color relationships in the early development of a composition. These Venetian artists developed a distinct language of sketchy, assured handling 9

FI GURE B Jean Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (French, 1758 -1846). View of a Bridge and the Town of Cava, Kingdom of Naples, 178$. Oil on paper mounted on canvas. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.55. for these paintings, in which form grew out of juxtapositions of color rather than line, a way of painting that came to characterize the oil sketch.3 At this early stage, oil sketches were not part of general teaching prac- tice, and painters did not employ them consistently Many artists continued to sketch in paint only as the underlayer for the final, finished work. Signifi- cantly painters used oil sketches to develop religious or history paintings— the traditionally more challenging and intellectual genres — rather than portraits, still lifes, or landscapes. (Oil sketches for these genres, especially landscape, would only emerge in the late eighteenth century [fig. B].) The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century oil sketch was thus much more closely linked to invenzione, or the cerebral and creative contribution of the artist, than to the spontaneous observation of nature. Already in the late sixteenth century artists had begun to use oil sketches to win their patrons' approval for large-scale works, and so these quickly executed paintings became instruments by which a patron could judge the viability of a larger project. This use of oil sketches in turn stemmed from the conditions of patronage emerging in the Counter-Reformation, which called for more careful attention to orthodox iconography and clear visual language.4 The oil sketches of Peter Paul Rubens (1577—1640) transformed oil sketches from functional objects, designed to project the form and meaning of the final work, into an independent mode that could itself be appreciated 5 as an independent work of art. Rubens's approach to oil sketches had twin 10

FIGURE c Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). The Miracles of Saint Francis ofPaola, ca. 1627-28. Oil on panel. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 9i.PB.$o. INTRODUCTION II

FIGURE D Pete? Paul Rubens. The Meeting of King Ferdinand III of Hungary and the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain at Nordlingen, 1635. Oil on panel. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 87.PB.i5. points of origin: his study with Otto van Veen—the first Flemish artist to paint independent preparatory works — and his later study in Italy. Rubens's sketches stand out from those of his predecessors for their remarkable vari- ation in size, color, degree of finish, use of underdrawing, and support (figs. C-D). As Julius Held has argued, Rubens's sketches were "never bound by 6 fixed rules of procedure/' and he painted them both for patrons and his own use. Rubens clearly thought quite highly of these works: in 1620, the artist jumped at the offer by the patrons of the Jesuit church in Antwerp to keep his thirty-nine sketches for the ceiling in his own possession, in exchange for 7 a new, full-scale altarpiece. Well aware of the value of his sketches, Rubens was the first painter whose oil sketches were collected aggressively during his own lifetime. They were prized not only by other artists but also by a wide range of collectors, not least because of the perception, often quite accurate, that the oil sketch represented the master's undiluted genius, unlike the finished work, which was often painted with studio assistants. By the eighteenth century the making of oil sketches had become com- mon practice among Italian, French, and Northern artists, who brought 8 these paintings to an extraordinarily high level of refinement. The shift had begun with Rubens; oil sketches were now seen as autonomous works of art and indices of the artist's brilliance and technical skill (figs. E-F). While the practical role of the oil sketch remained constant, artists and collec- tors increasingly praised the works for their aesthetic qualities. The French critic Denis Diderot extolled these paintings as being a more immediate 12

FIGURE E Placido Costanzi (Italian, ca. 1690-1759). The Immaculate Conception, ca. 1730. Oil on canvas. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 70.PA.42. FIGURE F Pompeo Batoni (Italian, 1708-1787). Christ in Glory with Saints Celsus, Julian, Marcionilla, and Basilissa, 1736-37. Oil on canvas. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 69.PA.3. INTRODUCTION 13

expression of the artist than the artifice of the final composition: "Why does a beautiful sketch please us more than a beautiful pictured It is because there is more life and fewer forms. As one introduces these forms, the life of it 9 disappears/' Claude-Henri Watelet's entry on sketches in the Encyclopedic (177$) extended this idea even further, seeing in the quick preparation of an oil sketch the mark of genius and individual personality: "It is this rapidity of execution which is the essential principle of the fire one sees ablaze in the esquisses, the sketches, of painters of genius: there one recognizes the mark left by the movement of their soul, one calculates its force and fruitful- 310 ness/ This increasingly modern critical attitude toward the painted sketch extended to Italy, and the 1731 remarks to Count Giacomo Tassi by Sebas- tiano Ricci — a painter who particularly influenced the young Tiepolo — have special significance. Ricci argued that the sketch was the primary work cc of art, with the final composition merely a reflection of the original: Your Excellency should know that there is a difference between a bozzetto, which bears the name ofmodello, and what you will be receiving. Because that is not a mere modello, but a completed picture. . . . You should also know that this small one is the original and the altarpiece is the copy/'11 It was from this tra- dition— surely instilled by Tiepolo's early training with Gregorio Lazzarini as well as close observation of artists such as Ricci and Giovanni Battista Piazzetta—that Tiepolo emerged. Today we appreciate oil sketches as spontaneous expressions of artistic inspiration, but these works held a complex position in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, often functioning simultaneously as artistic tools as well as expressive, collectible works of art. The word sketch in English retains this double meaning, on the one hand describing the work's purpose as a preparatory study while on the other referring to a loose and rapid manner of execution. This multivalency also appears in the early terminology de- scribing oil sketches. A vocabulary for these paintings only came into being slowly, with the first terms emerging from the language of drawing, for these paintings were understood initially as a subset of drawing instead of paint- 12 ing. For example, in one of the few references Rubens made to his own 13 sketches, he used the expression "dissegno colorito" derived from disegno ad olio, an Italian term for oil sketch used well into the seventeenth century. Rubens's term thus associates the oil sketch with disegno, or drawing. In Italian artistic theory, disegno refers to the intellectual component of making art, while the adjective colorito connects not only to the manual and corporeal aspects of art but also to the senses, indicating that Rubens considered oil sketches a tool to sharpen the intellectual content of a work as well as a concrete way to 14 establish color relationships. We nowadays distinguish between a bozzetto, or an initial idea laid out in paint, and a modello, a more elaborate, finished composition used by the artist in developing a larger work, but these terms only began to gain consis- tent use in the eighteenth century The Italian bozzetto derives from the verbs abbozzare and sbozzare, words used to describe roughing out a design in paint on a canvas. In actual practice, however, the words were used more loosely referring to both underpaint and independent preparatory works. In 1681, 14

Filippo Baldinucci sought to codify these shifting terms in his dictionary Vocabolario toscano dell'arte del disegno, reserving modello for sculpture and archi- 15 tecture and using bozza and abbozzo to describe independent oil sketches. Baldinucci used an additional term—macchia—to characterize "some draw- ings, as well as some paintings, made with extraordinary facility, and with harmony and freshness, without much ink or paint, and in such a way that they almost seem not made by the hand of artifice, but as if they appeared by 516 themselves on the page or canvas/ The advent of this term thus demon- strates the key shift in the perception of oil sketches in the later seventeenth century. By defining sketches not exclusively by function or medium but by the works' handling and relationship to the artist's mind, critics began to separate the oil sketch from the preliminary drawing and the final painting; ease of handling, freshness, and spontaneous brilliance became the defining and desired qualities. Tiepolo and the Oil Skettfi At the beginning of Tiepolo's career, oil sketches were standard practice among eighteenth-century Venetian painters, and his zeal for this type of painting was not unusual. Tiepolo's oil sketches, however, stood apart from those of his contemporaries by their assuredness, sophistication, inven- tiveness, and luxurious handling of paint. These qualities—which remained consistent for over fifty years — derived in part from the innovative way in which Tiepolo conceived of the oil sketch in the overall development of a work. While most eighteenth-century artists began large-scale composi- tions with preliminary drawings, only eventually working up to a painted oil sketch, Tiepolo reversed that process, beginning major works with an oil sketch and only later using drawings—which ranged from free ink and wash drawings to carefully finished sheets—to develop individual aspects of the entire composition. Likewise, while artists often executed multiple modelli for a large project, Tiepolo consistently painted a single complete sketch, rarely revealing palimpsests and overpainting (see cat. no. 12 for an unusual exception). For Tiepolo, the sense of the whole started with exploring color relationships; oil sketches were essential at the inception of a composition. Despite the clear relationship of oil sketches to drawing, the precise role of these paintings for Tiepolo is not always easy to determine, partly because the sketches could serve multiple purposes over time. Many of the Courtauld paintings were presentation sketches, such as the five modelli for the church of San Pascual Baylon in Aranjuez (cat. nos. 9—13), approved by King Charles III of Spain in 1767. With rare exceptions, patrons did not lay claim to these sketches, and they seem to have been perceived, like drawings, as the artist's property.17 Indeed, the oil sketches consistently remained in Tiepolo's studio throughout the development of the final composition, available for the artist and his assistants to consult. In other cases, especially for ceiling paintings, Tiepolo created sketches with more of an eye to devel- oping the finished composition in relation to the space where the fresco or INTRODUCTION 15

altarpiece would eventually be seen. As the Getty modello for the ceiling of Santa Maria degli Scalzi (cat. no. 8) demonstrates, oil sketches could even play a role in the dialogue between Tiepolo and other collaborators, such as Giro- lamo Mingozzi Colonna (ca. i688-ca. 1766), whose illusionistic architecture often accompanied Tiepolo's frescoes. Works retained by Tiepolo could also enjoy a second life as a salable commodity, such as the sketches sold to the 18 Swedish collector Count Carl Gustav Tessin. He also regularly gave away oil sketches as gifts to clients, colleagues, and friends, such as the works Tiepolo presented to his great advocate, the critic Count Francesco Algarotti.19 Sketches made as ricordi, or copies after the original composition, re- 20 main controversial. That Tiepolo's studio made such copies is not in doubt, but scholars disagree as to whether Tiepolo would have produced such works himself (although the high quality and poised handling of the oil sketch rep- resenting a ceiling from the Palazzo Archinto in Milan [cat. no. 4] surely comes from Tiepolo's own hand). At the same time, many ricordi are clearly studio copies, exercises Tiepolo—to judge from the number of such works in circulation—enthusiastically encouraged, both as records of projects in far- flung locations and as part of his pupils' education. These copies evidently enjoyed a large resale market, and his sons Giandomenico (1727—1804) and Lorenzo (1736-1772), as well as another pupil, Giovanni Raggi (1712- 1792/94), emulated his oil sketches with convincing, salable results.21 Collecting Oil Sketfaes 22 Most oil sketches—like drawings—remained in painters' studios. These paintings served as pedagogic tools, guides for realizing a larger composition awarded to the studio, or j ump ing -off points to develop related compositions, practices often continued after the death of the master. Ap- preciation of oil sketches by art collectors began in the early seventeenth century and swelled over the next two hundred years. The transformation of 3 these paintings from artists tools to treasured objects was inextricably tied to the growing understanding of oil sketches as distillations of an artist's unique genius. The excitement of the fresh, painterly surfaces became an end in itself, and the works were prized for their closeness to the hand and mind of the artist.23 While many collectors competed for oil sketches by Rubens, such broad enthusiasm for modelli by other artists remained unusual at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and a small number of figures, such as Carlo, Leopoldo, and Ferdinando de' Medici, as well as Pietro Aldobrandini, domi- nated the market. Even for these well-known collectors, oil sketches played a relatively minor role in their overall patronage. Symptomatic of this dis- regard, the seventeenth-century theorist Gian Pietro Bellori ignored oil sketches throughout his Le vite de pittori, scultori, e architetti moderni, even in his biography of Rubens.24 Eighteenth-century collectors and dealers sparked interest in the oil sketch, particularly in Venice. This new enthusiasm for modelli reflected a 16

growing taste for a spontaneous style of, painting, exemplified by such sophisticated collectors as Tessin and Algarotti, who grouped oil sketches 25 together with loosely painted easel pictures. Oil sketches also proved ex- tremely popular among connoisseurs from the Veneto, such as Giovanni Vianello and Giuseppe Toninotto, who developed important collections of 26 these paintings. The Venetian collector and dealer Giovanni Maria Sasso was the most powerful figure in this shift in taste. His collection included drawings and painted sketches by such artists as Giambattista and Gian- domenico Tiepolo, Sebastiano Ricci, Giambattista Pittoni, and Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, and he developed a market for these works, fostering clients in the Veneto and abroad. Recent research on one of these collectors, Sir Abraham Hume, has revealed that for Hume and Sasso the category of modello was extremely broad, incorporating oil sketches, colored drawings, and other types of works—including highly polished, reduced copies — indicating the continuing fluidity of the category even into the nineteenth 27 century Tiepolo's oil sketches largely remained in his studio throughout his life. Although he occasionally sold these paintings, he bestowed others as gifts, including the Courtauld Saint Luigi Gonzaga in Glory (cat. no. 3), which he pre- sented to the family of a recently deceased colleague, indicating that Tiepolo himself valued these works as more than studio tools. Other patrons, nota- bly Algarotti, also commissioned ricordi from the artist, although in many cases these paintings came from the studio rather than Tiepolo himself28 Far more oil sketches entered the market after Tiepolo's death in 1770, when his son Giandomenico inherited the numerous remaining paintings and drawings in his father's studio. The Spanish painter Francisco Bayeu owned Tiepolo's sketches for the Aranjuez altarpieces from 1770 until his death in 1795 (cat. nos. 9—13A), suggesting that Giandomenico began selling sketches even before his return to Venice, and he certainly sold paintings to dealers, including Giovanni Maria Sasso. Giandomenico—who surely used his father's sketches in his own prac- tice as a painter — still owned a substantial number of these sketches even after 1800, to judge from the acquisition of five such works by the sculptor Antonio Canova, including one version of the sketch for the ceiling of Santa 29 Maria degli Scalzi (see cat. no. $). The dispersion escalated after Giando- menico's death in 1804, when, for example, the Venetian dealer Niccolo Leo- nelli exported twenty oil sketches by Giambattista Tiepolo to St. Petersburg in i8i4.3° Tiepolo Oil Sket&es at the Courtauld The remarkable collection of works by Tiepolo at the Courtauld, includ- ing the twelve paintings in this exhibition, stand among the signal holdings of the institution. Count Antoine Seilern (1901-1978) assembled these canvases, which form part of his 1978 bequest of 492 works of art to 31 the Courtauld Institute of Art as the Princes Gate Collection. Seilern's INTRODUCTION YJ

holdings range from the early Italian Renaissance through the mid-twentieth century, but his taste is best characterized by his small, highly refined paint- ings and drawings that date from the mid-sixteenth through the late eigh- teenth century Seilern began studying art at Vienna University in 1933, and his activi- ties as a serious collector also began around this time. His first scholarly and collecting activities centered on the work of Peter Paul Rubens, and his early absorption in the colorism of this painter foreshadowed his interest in Vene- tian art (Seilern eventually owned works by Tintoretto, Palma il Vecchio, and Titian) and led directly to his interest in Tiepolo. Seilern bought his first oil sketch by Rubens in 1933, launching a special interest in the working practices of artists. His collection contained numerous examples spanning the history of the oil sketch, including an important early sketch by Poli- doro da Caravaggio, as well as striking works by van Dyck, Grayer, Pittoni, and Sebastiano Ricci. Seilern acquired his first two oil sketches by Tiepolo in 1937 (cat. nos. 9 and n), and he quickly aimed to create a broad collection of the artist's modelli. In some cases, such as the Aranjuez sketches (cat. nos. 9-I3A), Seilern sought completeness, acquiring all five painted sketches (and one drawing) by 1967; he always selected pictures of exceptional refinement and quality, advised by the Tiepolo scholar James Byam Shaw. Seilern expanded beyond the category of oil sketches in only two cases, the similarly scaled devotional picture of Saint Rocco (cat. no. $A) and a small fragment of an altarpiece related to the sketch Saint Joseph with the Christ Child (cat. no. 136). Seilern produced extensive scholarship on his collection, which sur- vives in the catalogues he published as well as in his extensive notes housed 32 in the Courtauld archives. In these writings, remarkable for their thor- oughness and modest, reflective tone, his enthusiasm, knowledge, and pre- science reveal a keen understanding and appreciation of the works of Tiepolo. Seilern participated in a larger movement in the mid-twentieth century to recuperate oil sketches not only into the larger understanding of an artist's production but also as a way to understand an artist's work as an 33 active intellectual process. Beyond the radiant beauty of Seilern's oil sketches by Tiepolo, the collection as a whole argues for the artist's intellect, presenting Tiepolo as not only a brilliant technician but an active mind, thoughtfully considering the most suitable form for the complex subjects of these pictures. 18

NOTE S 1 Our understanding of the role of the early The Ceiling Paintings for the Jesuit Church in modern oil sketch has been amplified Antwerp (London: Phaidon, 1968). considerably in the past thirty years, thanks 8 For the French tradition of oil sketches, especially to the landmark studies of see French Oil Sketches from the Los Angeles Linda Freeman Bauer and Oreste Ferrari. County Museum of Art: Seventeenth Century- See especially Linda Freeman Bauer, Nineteenth Century. Los Angeles: Ahmanson "On the Origins of the Oil Sketch: Form Foundation, 2002, especially the essay and Function in Cinquecento Preparatory by J. Patrice Marandel, "A Taste for Oil Techniques/' Ph.D. diss., New York Sketches," ix-xiv. University 197$; Linda Freeman Bauer, "'Quanto si disegna si dipinge ancora': 9 Denis Diderot, Salons, 3:1767, edited by Some Observations on the Oil Sketch," Jean Seznec and Jean Adhemar (Oxford: Storia delVarte 32 (1978): 45-57; Oreste Clarendon Press, 1963), 241: "Pourquoi Ferrari, Bozzetti italiani dal manerismo une belle esquisse nous plait-elle plus al barocco (Naples: Electa, 1990); Oreste qu'un beau tableau? C'est qu'il y a plus de Ferrari, "The Development of the Oil vie et moins de formes. A mesure qu'on Sketch in Italy," in Brown 1993, 42-63; and introduit les formes la vie disparait." Linda Bauer and George Bauer, "Artists' 10 "Esquisse," Encyclopedic ou dictionnaire Inventories and the Language of the Oil raisonne des sciences, des arts, et des metiers Sketch," Burlington Magazine 141, no. 1158 (Paris, 1775). Translated in Ferrari 1993, 63. (September 1999): 520-30. Other impor- tant studies include Bruno Buschart, "Die 11 Bottari and Ticozzi 1822, 4: 93-94: "Sappia deutsche Olskizze des 18. Jahrhunderts als VS. 111.ma che vi e differenza da un autonomes Kunstwerk," Munchner Jahrbuch bozzetto, che porta il nome di modello, e des bildenden Kunst 15 (1964): 145-76; quello che le peverra. Perche questo non Masters of the Loaded Brush: Oil Sketches e modello solo, ma quadro terminato . . . from Rubens to Tiepolo, exhibition catalogue sappia di piu che questo piccolo e originale (New York: N.p., 1967); and Riidiger e la tavola d'altare e la copia." Translated Klessmann, ed., Beitrdge zur Geschichte in Ferrari 1993, 61. Also, consider Ricci's der Olskizze von 16. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert, slightly earlier words to Tassi, which exhibition catalogue (Braunschweig: indicate the patron's interest in possessing Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, 1984). an oil sketch that is a beautiful object in 2 Ferrari 1993, 42-43. itself: "II modello della consaputo tavola e terminato; e siccome VS. illustriss. bramava 3 Bauer 1975, ch. 3; Ferrari 1993, 59. che fosse piu bello della tavola stessa, 4 Ferrari 1993, 47~49- credo che ne avera 1'intento, essendomi veramente riuscito in conformita di quello 5 The primary source on Rubens oil sketches che bramava" (Bottari and Ticozzi 1822, remains Julius S. Held, The Oil Sketches of 4:91). Peter Paul Rubens: A Critical Catalogue, 2 vols. 12 As Linda Bauer and George Bauer (1999) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, have noted, this phenomenon is consistent 1980), especially 1:3-18. Also see Peter across Europe, reflected in the vocabulary Sutton and Marjorie Wieseman, Drawn by in use at the beginning of the seventeenth the Brush: Oil Sketches by Peter Paul Rubens, century: disegno, dessin, and tekeningen. exhibition catalogue (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004). For an alternative 13 Peter Paul Rubens to Archduke Albert, approach to oil sketches in the north, see March 19, 1614, in The Letters of Peter Paul Ronni Baer, "Rembrandt's Oil Sketches," in Rubens, translated and edited by Ruth Rembrandt's Journey. Painter—Draftsman— Saunders Magurn (Cambridge, MA: Etcher, exhibition catalogue, edited by Harvard University Press, 1955), 56. Clifford S. Ackley (Boston: MFA Publi- 14 Joanna Woodall, "Drawing in Color," in cations, 2003), 29-44. Cuno 2003, 9-11. 6 Held 1980, 4. 15 Baldinucci 1681. For the complexity of 7 On the Jesuit church sketches, see Held meanings for these terms in seventeenth- 1980, 33—62; and John Rupert Martin, century Italy, see especially Bauer and Bauer 1999. INTRODUCTION 19

16 "D'alcuni disegni, ed alcuna volta anche 25 Brown 1993, 19-20. For more generally pitture, fatte con istraordinaria facilita, on the taste for loose, painterly brushwork, e con un tale accordamento e freschezza, see Philip Sohm, Pittoresco: Marco Boschini, senza niolta matita o colore, e in tal modo His Critics and Their Critiques of Painterly che quasi pare, che ella non da mano Brushwork in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth- d'Artefice, ma da per se stessa sia apparita Century Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge sul foglio o su la tela, e dicono: questo e University Press, 1991), especially 1-62. una bella macchia" (Baldinucci 1681, 86). 26 Francis Haskell, Patrons and Painters: 17 Beverly Louise Brown, "In Search A Study in the Relations between Italian Art and of the Prima idea: The Oil Sketches of Society in the Age of the Baroque (New Haven: Giambattista Tiepolo," in Brown 1993, 19. Yale University Press, 1980), 373-76. 18 Brown 1993, 19-20. 27 I am grateful to Linda Borean for sharing 19 Levey I96ob, 250-53. aspects of her important forthcoming study of Sir Abraham Hume, Giovanni 20 Beverly Louise Brown (1993, 17) cites a Maria Sasso, and Giovanni Antonio 1760 letter from Tiepolo to Cardinal Armano, from which these observations Daniele Dolfin in which Tiepolo noted derive. that before the commissioned modelli 28 Brown 1993, 19-20; Levey I96ob. could be sent for inspection, they needed to be copied in the studio. 29 Pavanello 1996, 7-75. A cousin of 21 Brown 1993, 18. Giandomenico, Ferdinando Tonioli, played a key role in the transactions with Canova, 22 This phenomenon is well documented further underscoring the importance of from artists' estate inventories. See Ferrari family networks in these sales (as well as !993> $6; and especially Linda Freeman the popularity of Giambattista Tiepolo's Bauer, "Oil Sketches, Unfinished Paintings, oil sketches among artists). and the Inventories of Artists' Estates," 30 Burton Fredericksen, "Niccolo Leonelli in Light on the Eternal City: Observations and the Export of Tiepolo Sketches to and Discoveries in the Art and Architecture of Russia," Burlington Magazine 144, no. 1195 Rome, edited by Hellmut Hager and (October 2002): 621-25. Susan Scott Munshower (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 1987). 31 This section depends heavily on the Linda Bauer notes the considerable important study of Seilern's collection by semantic challenges in determining from Helen Braham. See the introduction to inventories the difference between oil Braham 1981, as well as Ernst Vegelin van sketches and unfinished paintings. Claerbergen, "'Everything connected with Nonetheless, the inventories appear to be Rubens interests me': Collecting Rubens' consistently peppered with oil sketches. Oil Sketches: The Case of Count Antoine 23 Bauer 1978, 45. Seilern," in Cuno 2003, 23—30. 24 Ferrari 1993, 56; Giovan Pietro Bellori, 32 Seilern 1959; Seilern 1969; Seilern I97ia; Le vite de pittori, scultori, e architetti Seilern I97ib. moderni, edited by Evelina Borea 33 Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen, "'Every- (Turin: Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1976); thing connected with Rubens interests for Rubens see 237-68. me': Collecting Rubens' Oil Sketches: The Case of Count Antoine Seilern," in Cuno 2003, 26-27. 20

Catalogue

I Allegory of the Power of Eloquence ca. 1725 Oil on canvas 5 46.5 x 67.5 cm (18% x 26 /s in.) The Samuel Courtaulct Trust at the Courtauld Institute Gallery, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; inv. 340 PROVENANCE EXHIBITIONS 1989, 167-68, fig. 97; Bradford and Private collection, Madrid; None. Braham 1989, 24; Farr, Bradford, and Hiigelshofer, Zurich, by 1955; sold to Braham 1990, 68, 69 (illus.); Brunei Count Antoine Seilern (1901-1978), BIBLIOGRAPHY 1991, $6 (as "collection privee"); London, 1959; by bequest to the Home Brown 1993, 201, fig. 89; Gemin and House Trustees for the Courtauld Morassi I955b, 4—7, figs. 2, 4—6; Piovene Pedrocco 1993, 245; Knox 1993, 135-37, Institute of Art, University of London, and Pallucchini 1968, 89, fig. 32; Seilern fig. 2; Pedrocco 2002, 208-9, fig- 52.1.a. 1978. 1969, 27, pi. XXX; Braham 1981, 72, fig. 105; Levey 1986, 23-24, fig. 30; Farr 1987, 62^63 (illus.); Barcham THIS PAINTING IS THE INITIAL SKETCH Amphion building the walls of Thebes with his for the ceiling of the main salone of music. Amphion—the son of Zeus and Antiope, the Palazzo Sandi in Venice (fig. i.i). Tommaso the queen of Thebes—was abandoned at birth Sandi, a powerful Venetian lawyer, launched and raised by shepherds, and through the tutelage a major renovation of the palazzo in 1721 under of Mercury he became a remarkable musician. the direction of the architect Domenico Rossi. When Amphion and his twin brother, Zethus, Despite a paucity of documentation, scholars sought out their mother as adults, they discovered have consistently dated the frescoes to 1725-26 her mistreatment at the hands of their uncle and for stylistic reasons, placing them between the his wife. Overthrowing Antiope's tormentors, presumed end of the construction of the palazzo they assumed power over Thebes and sought to in 1725 and the start of Tiepolo's work in Udine fortify the city. Amphion began to play his lyre, the following year.1 and through the sheer power of his music The first reference to the fresco, Tiepolo's the stones flew through the air and moved into first major ceiling commission, comes only place. As in all the scenes in Tiepolo's sketch, in 1732, when Vincenzo da Canal described the the figures, seen di sotto in su, rise from the cor- work as four stories illustrating the power nice line. Amphion stands on an outcrop at 2 of eloquence. Tiepolo painted several mytho- left, wrapped in a blue windswept cloak (a detail logical scenes on canvas for the walls below;3 the artist picked out in lapis, in contrast to the the comission also involved a collaboration with Prussian blue used elsewhere on the canvas). Nicolo Bambini, who executed the frieze of He stands before the viewer, confidently plucking grotesques beneath the ceiling and the walls and his lyre, and turns back to behold the masonry contributed two wall paintings.4 his music sends flying through the air, con- In the sketch, Minerva and Mercury—gods structing a gleaming white fortification, while of reason, wisdom, and eloquence—preside spectators point, gaping in surprise. at center over four mythological scenes that sur- Orpheus claiming Eurydice from Hades round the edges of the rectangular canvas. appears at bottom. Best known from Ovid's ver- On the right appears a subject well known from sion in the Metamorphoses (10:53-63), Orpheus, such classical sources as Apollodorus's Library another remarkable musician trained by Mercury, (3:5:5-6) but unprecedented in painting, descended into Hades hoping to reclaim his 22

CAT. NO. I 23

FIGURE i.i Giambattista Tiepolo. Allegory of the Power of Eloquence, 1725-26. Fresco. Venice, Palazzo Sandi. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York. wife, Eurydice, who had been killed by a snakebite. him by chains. Antonio Morassi, who first pub- With music so moving it brought even the Furies lished the sketch in 1955, identified this scene as to tears, Orpheus persuaded Pluto to release 5 Hercules and the chained Cercopes. The Eurydice, which the god granted on the condition Cercopes were gnomes whom Hercules seized that Orpheus not gaze upon her until he had and carried away in chains after they attempted passed Cerberus at the gates of the underworld. to rob him. Dangling behind his back, the In Tiepolo's sketch, Orpheus—supporting his 5 Cercopes joked about their view—Hercules wife with one hand and raising a stringed instru- hairy and sunburned buttocks — and their witty ment with the other—crosses the rocks near comments caused the hero to laugh so uproari- the exit of Hades, with its menacing dark cloud, ously that he agreed to free them. while the three-headed Cerberus barks fiercely While the story lends itself to the overall in front of them. Tiepolo thus presents the theme of eloquence, the large crowd of figures, charged moment just before Orpheus, fearing Hercules' lack of amusement, and the position that Eurydice might falter on the rocky path, of the chains indicate another story Hercules glances back at his wife and loses her forever. Gallicus captivating his audience. This ancient Across from Amphion appears the strap- Celtic tradition, first described by Lucian in ping figure of Hercules, clad in animal skins, who Herakles: An Introduction, casts Hercules, rather strides above eight prostrate figures attached to than Mercury, as the god of eloquence and 24

had been represented emblematically by Hercules Scholars have gradually worked out the dragging his listeners with chains attached from interpretation of the ceiling and the sources for his mouth to his audience's ears. Artists such the unusual combination of myths. The stories as Albrecht Durer depicted the story and it all come from common ancient texts, but appeared regularly in Renaissance literature, the chief sources are emblem books, suggesting 10 including the widely published Imagini degli dei a highly literary unifying theme. That degli antichi of Vincenzo Cartari.6 Tiepolo, theme may have been eloquence, an especially typically strayed far from the early sources and appropriate subject for the Sandi family, who did a free variation on the print tradition to made their fortune through the law and n create an image better suited to an illusionistic were ennobled in 1685. In this interpretation, ceiling. In the sketch the figures expand hori- Hercules and Amphion directly exemplify zontally across the ceiling, with Hercules at the eloquence, Orpheus implies it indirectly, and acme of a low pyramid of figures. Tiepolo also Bellerophon represents the general triumph 12 alters the standard interpretation, depicting of civilization and culture. Sandi patronage the chains attached more plausibly to the hero's demands further study and should ultimately 13 neck and hands. provide the key to the program. While the The final image in the sketch depicts a com- iconography no doubt bears some relation to mon myth, Bellerophon attacking the monstrous the legal profession that secured the Sandi Chimaera while mounted on Pegasus, the flying their wealth and noble status, the ceiling stands steed provided him by Minerva. Tiepolo presents apart from other eighteenth-century Venetian the horse and rider at a particularly startling frescoes in not openly glorifying the family angle, rearing to charge the monster. The subject name, suggesting a highly specific intellectual appears infrequently in painting, and Tiepolo program in play14 again drew on the emblematic tradition for his Music may also be a more important orga- imagery: the motif of Bellerophon attacking nizing theme than previously acknowledged. the Chimaera with a branch derives from a print In revising the sketch Tiepolo placed the two first published by Andrea Alciati in the sixteenth musical subjects in primary position and 7 substituted a contemporary stringed instrument century This composition is the first extant oil for Orpheus's traditional lute. While the sub- sketch by Tiepolo for a ceiling painting and rep- jects were all atypical for painters to represent resents an early stage in his development as and certainly never appeared together, Amphion, 8 Orpheus, and Bellerophon were all common a ceiling frescoist. He pushes each scene to the margins of the composition, where each pyra- subjects in early modern music, including cele- midal vignette stands on an independent bit brated compositions such as Carlo Grossf s of landscape, in turn connected to the architec- chamber work L'Amphione, first performed tural frame of the salone, with the sky opening in Venice in 1675; Antonio Draghi's 1682 opera up behind each group. Tiepolo revised this La Chimera; Paolo Magni's 1698 opera L'Amphione; composition considerably in the fresco, most and Jean-Philippe Rameau's 1721 cantata significantly by rearranging the order of Orphee.^ & the stories, placing Orpheus and Eurydice across from Amphion on the long walls, and placing Bellerophon opposite Hercules Gallicus on the NOTES short wall.9 He also increased the proportions of the figures, highlighting the gods at center 1 For detailed analysis of the palazzo and frescoes, see Knox 1993. through a burst of white light and a whorl 2 Vincenzo da Canal, 1732 manuscript published as Vita of clouds. In painting the ceiling Tiepolo shifted di Gregorio Lazzarini (Vinegia: Palese, 1809), XXXII: his palette considerably, moving from the "Dipinse a Venezia nel palazzo Sandi il sojfitto della sola in quattro warm tones of the sketch (derived from the thin stork indicanti la Eloquenza sotto altrijeroglifici." 3 Achilles among the Daughters ofLycomedes, Apollo and Marsjas, application of paint over the reddish ground) and Hercules and Antaeus, now in the da Schio collection, to the bright, saturated colors of the fresco. Castelgomberto, Vicenza. ALLEGORY OF THE POWER OF ELOQJJENCE 25

4 Veturia and Volumnia Appealing to Coriolanus and The Three decorations for the room, also viewed the ceiling as an Graces, now in the da Schio collection, Castelgomberto, exemplum virtutis for the marriage of Tommaso Sandi's Vicenza. son, Vettor, in 1724. Aikema's thesis, however, depends 5 Antonio Morassi (i95$b, 4). Bernard Aikema (1986, on a misreading of the date of the wedding. I7in.n) and Filippo Pedrocco (2002, 280) have 13 For example, Christopher Drew Armstrong has pro- reaffirmed this interpretation. posed an important new interpretation of the ico- 6 Vincenzo Cartari, Le imagini degli dei degli antichi nography, rooted in Giovanni Battista Vice's theories (Venice: Vincentio Valgrisi, 1571), 341. of history and natural law, first outlined in a lecture, 7 Andrea Alciati, Emblematum liber (Paris: Christiani "Myth and Enlightenment: Tiepolo and the New Wecheli, 1542), 226-27. Science," University College, University of Toronto, 8 Brown 1993, 201. March 17, 2004 (to be published in a forthcoming 9 As Antonio Morassi first observed (i9$$b, 7), Tiepolo article). For important insights into the intellectual probably reworked the Hercules scene much later, interests of the Sandi family, see Francesco dalla perhaps on account of some damage to the original, Colletta, I principi di storia civile di Vettor Sandi: Diritto, which explains the more even handling of light and the istituzioni, e storia nella Venezia de metd Settecento (Venice: neater contours of the figures, connected to his much Istituto veneto di scienza, lettere, e arti, 1995). later style, perhaps post-1753. 14 Knox 1993, 141. 10 Knox 1993, 135-37. 15 See entries in The Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in 11 Knox 1993, 135; and Levey 1986, 23. the Arts. Pegasus held a crucial position in Arcadian 12 Others have interpreted the theme even more broadly poetics, suggesting a possible connection of the Sandi with Michael Levey (1986, 23) considering the work to Arcadian circles. See, for example, Liliana Barroero as centering on the notion of ingenuity Bernard and Stefano Susinno, "Arcadian Rome: Universal Aikema (1986, 167), connecting the ceiling with the full Capital of the Arts," in Bowron and Rishel 2000, 52. 26

2 The Madonna of the Rosary ca. 1727-29 Oil on canvas 3 3 44.2 x 23.9 cm (i7 /s x 9 /s in.) The Samuel Courtauld Trust at the Courtauld Institute Gallery, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; inv. 341 PROVENANCE EXHIBITIONS an Angel); Barcham 1989,164,166,168, Jaffe, Berlin; private collection, Venice and New York 1996, no. 3ob. fig. 96 (as The Madonna and Child with Bergamo, Italy, by 1962-64; sold to an Angel); Bradford and Braham 1989, 2$ (as The Madonna and Child with Count Antoine Seilern (1901-1978), BIBLIOGRAPHY an Angel); Gemin and Pedrocco 1993, London, 1964; by bequest to the Home Thieme-Becker 1939, 147; Morassi 249, fig. 73 (as Madonna con bambino e House Trustees for the Courtauld 1962, 4, 19, fig. 80 (as Madonna and angeli); Christiansen 1996, 205, 207-8, Institute of Art, University of London, Child with an Angel); Piovene and fig. 3ob; Pedrocco 2002, 209, fig. 55 1978. Pallucchini 1968, 90-91, fig. 41 (as (as Madonna col bambino e angeli). Madonna col bambino e un angelo); Seilern 1969, 28, pi. XXI (as Madonna and Child with an Angel); Braham 1981, 73, fig. 107 (as The Madonna and Child with AMONUMENTAL STATUE COME TO LIFE, blue reflections of the blue cloth in the cloud the Virgin steps forward grandly and on the white fabric held by the Virgin. from a niche, presenting the Christ Child to the Likewise, Tiepolo portrays Mary in a red-orange beholder while an angel kneels humbly before gown, shot through with bravura strokes of them. The infant Jesus gazes out with curious white and canary yellow. intensity sweetly mimicking the Virgin's Antonio Morassi first connected the painting stance and her outstretched arm. He stands on to a small altarpiece, documented to 1735 (fig. a cerulean cloth held by his mother, as well 2.x).1 Subsequent scholars have generally agreed as a cloud supported by two putti. Both mother that the sketch dates to an earlier mode in and son hold rosaries: the Virgin's coral beads Tiepolo's career, around the time of his work in flicker in the shadows at right, while Christ's Udine, since the sharp color contrasts and spiky golden rosary gleams brightly proffered to the figures recall the artist's early inspiration from viewer. 2 Giovanni Battista Piazzetta. Although the altar- This work beautifully demonstrates the piece takes its basic format and color scheme brilliant technique Tiepolo brought to his oil from the oil sketch—particularly in the figure sketches. The coloristic richness of this painting of the statuesque Virgin—the changes between depends on the artist's deft and economic use of the early painting and the final work are con- ground layers. Tiepolo prepared the canvas with siderable, demonstrating a major stylistic and a warm reddish brown ground, followed by a conceptual break between the two images. stratum of cool blue-gray. He then incorporated The altarpiece strikes a more ecclesiastical note, these layers in the overall palette, using them, marked by the angel's transformation into an for example, to describe the faces and the niche's acolyte carrying an incense burner. It also has a frieze. Less interested in precise anatomical more personal tone, with Tiepolo lowering description than in defining form through color, the viewpoint slightly and placing the Madonna Tiepolo employed bold passages of wet-on-wet solidly on the ground. Moreover, the final work paint, such as the lemon, ice blue, and rust emphasizes the Madonna's role in presenting strokes of the angel's shoulder, or the greenish the gift of the rosary to humanity, as well as her 27

CAT. NO. 2 28

well as the contrast between the tender infant and the grave expression of the Virgin—thus speaks directly to the rosary. According to legend, Saint Dominic (ca. 1170-1221) initiated the practice of the rosary, which he received from the Virgin in a vision. Historically, however, the rosary developed out of Marian devotions in the twelfth century and—influenced by the Dominican order — its use was widespread by the fifteenth century. In the eighteenth century the rosary enjoyed newfound popularity under the Dominican pope Benedict XIII Orsini (r. 1724-30), who extended the feast of the rosary to all Roman Catholics in 1726. For this reason the painting may connect to Dominican patrons, perhaps a Dominican church or a related con- fraternity. Given that the rosary functioned as a means to grace and an instrument of communal, controlled prayer, the image may have partic- ularly appealed to patrons participating in the revival of traditional, Counter-Reformation values in the early eighteenth century Certainly the renewed interest in the rosary under Benedict XIII argues for an early dating for the sketch. Tiepolo may well have executed this modello on a currently popular devotional FIGURE 2.1 GiambattistaTiepolo. The Madonna of the Rosary, theme in the hope of attracting patrons, rather than as a study for a specific commission.4 173$. Oil on canvas. Private collection. He may have turned back to the sketch years later as the jumping-off point for the full-scale role as intercessor. Tiepolo moves the Virgin's altarpiece. & arm forward and picks out her hand with light. All the central figures train their attention on her rosary, and Christ holds a small cross instead NOTES of beads. Tiepolo also moves away from the dramatic color relationships and startling con- 1 Morassi 1962, 4. trasts of light and dark so crucial to the sketch, 2 The earlier dating was first proposed in Piovene and Pallucchini 1968, 90-91. toward the more even lighting and more blended 3 For more on the connection of the cult of the rosary color scheme that mark the finished work. and the visual arts, see especially Esperanca Maria The rosary, an exercise in mental and vocal Camara, "Pictures and Prayers: Madonna of the prayer, involves the repetitive recitation of Rosary Imagery in Post-Tridentine Italy" Ph.D. diss., the Hail Mary while meditating on the life of The Johns Hopkins University 2003. 4 Entry by Catherine Whistler in Christiansen 1996, 3 Christ. Mary's centrality in both images — as 205-8. THE MADONNA OF THE ROSARY 29

3 Saint Luigi Gonzaga in Glory ca. 1728-29 Oil on canvas 5 58 x 44.7 cm (22/8 x i7 /s in.) The Samuel Courtauld Trust at the Courtauld Institute Gallery, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; inv. 170 PROVENANCE EXHIBITIONS 73, fig. 106; Martini 1988, 154, no. 10, Probably the heirs of Andrea Fantoni London 1954-55, no. 478; London 1960, fig. 4; Barcham 1989, 164, 168, pi. V; (1659-1734), 1735; by inheritance within no. 411. Bradford and Braham 1989, 25; Farr, the Fantoni family Casa Fantoni, Bradford, and Braham 1990, 72 (illus.); Gemin and Pedrocco 1993, 249, fig. 74; Rovetta, near Bergamo; sold through BIBLIOGRAPHY Pedrocco 2002, 209, fig. 57. W Burchardt to Count Antoine Fiocco 1938, 152; Morassi 1938, 141-42, Seilern (1901-1978), London, 1953; by frontispiece; Watson 1955, 262, 264, bequest to the Home House Trustees fig. 298; Seilern 1959, 159, pis. CXXXII, for the Courtauld Institute of Art, CXXXIII; Morassi 1962, 20, fig. 113; University of London, 1978. Piovene and Pallucchini 1968, 91, fig. 44; Seilern I97ia, 57; Braham 1981, HELD ALOFT BY A GROUP OF PUTTI, his slenderness, youth, and overpowering super- the Host rises on a cloud before Luigi natural experience, and the artist intensifies the (Aloysius) Gonzaga (1568-1591). The young young man's gray pallor through the intense Jesuit throws his head back and closes his white of his robe and the spectrum of pinks that eyes, in the throes of an ecstatic vision. Clad in appear on the fleshy angels surrounding him. swirls of fabric, three angels accompany him, Born into one of Italy's most illustrious noble and they—along with the putti at lower right— families, Luigi Gonzaga came under the spiritual bear garlands, crowns, and scepters, signaling guidance of Charles Borromeo at the age of the majesty of the event. The open book on twelve. In 1585 he renounced his inheritance and the steps suggests that the young man's prayers entered the Jesuit order in Rome as a novice, have been interrupted, but the event takes energetically devoting himself to Christian ser- place in an entirely fantastic Veronesian setting, vice, most remarkably by nursing the sick during conveying the overwhelming grandeur of Luigi the 1591 outbreak of plague in Rome. Always Gonzaga's rapture. A sculpture of Faith—the physically weak, Luigi died at the age of twenty- only figure touching the ground in the painting three and immediately became a beloved popular —underscores the profound belief that fuels religious figure and one of the best-known Jesuits. this vision, but the oil sketch accentuates above Representations of the saint began to all the high emotional key and otherworldliness appear frequently in the Veneto during the late of the scene. The vivid contrasts of dark and 17208, for example, in altarpieces by Antonio light around the perimeter of the canvas empha- Balestra and Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, size the spectacular nature of the event, and an interest surely sparked by his canonization in the peculiar perspective, especially the exagger- late 1726 and the 1729 declaration of the saint ated tilt into space created by the pattern as patron to youth by Pope Benedict XIII Orsini of floor tiles, further transports the event into (r. 1724-30). the spiritual, rather than the material, realm. In its depiction of a mystical experience, Tiepolo elongates the proportions of all the this image stands squarely at the center of funda- figures, especially Luigi Gonzaga, emphasizing mental religious debates in eighteenth-century 30

CAT. NO. 3 31

Italy between advocates of visionary, emotive Glory dates to the late 17208. Its handling recalls spirituality and supporters of regolata devozione, another early sketch, The Martyrdom of Saint or the moderated, Enlightenment-influenced Agatha (cat. no. 6), a similar work difficult to movement, supported by such rationalist reform- align with a major commission of the late 17208. ers as Ludovico Antonio Muratori. Tiepolo's Tiepolo received few altarpiece commissions altarpiece charts a middle ground, demonstrating early in his career, and so another possibility is the young artist's already keen sensitivity to that Tiepolo executed this work on speculation complex ecclesiastical arguments. Rather than in order to present his skills as a major ecclesi- represent a specific moment in the young saint's astical painter. life, Tiepolo concentrates on Luigi Gonzaga's An inscription on the verso, GIO : BATTISTA ; well-known devotion to the Eucharist, in this TIEPOLO 1735, connects the painting to the fam- way identifying him with a fundamental Christian ily of the sculptor Andrea Fantoni (1659-1734), sacrament and allying the new saint with main- who worked with Tiepolo on the sculpted frame stream Catholicism. On the other hand, the surrounding the painter's 1734 high altar of the ahistoricism, tenderness, and evanescence of this Ognissanti in Rovetta. However, this inscription work reaffirm the values of a mystic, popular surely refers to the date he presented the sketch spirituality1 to the family rather than to the date of execu- The purpose of this sketch remains unclear, tion.3 This work thus demonstrates how Tiepolo and no known drawings, paintings, or documents could sometimes use an oil sketch, first as relate to it. The painting possibly functioned an object retained in the studio, then as a gift to as a modello for an altarpiece or other religious a friend and colleague, a token of the close painting that Tiepolo never executed, perhaps working relationship between the two men. & commissioned in the outpouring of interest caused by the saint's recent canonization. The exaggerated perspective and the use of illu- NOTES sionistic sculpture connect the work to one of Tiepolo's most celebrated early projects, the 1 For more on these fundamental debates, see Rosa 1999, frescoes in the Palazzo Patricale in Udine,2 47-57- 2 Pedrocco 2002, 212-14. another indication that Saint Luigi Gonzaga in 3 Morassi 1938, 142. 32

4 Apollo and Phaethon ca. 1731 Oil on canvas 64.1 x 47.6 cm (25/4 x 18% in.) Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.86.257 PROVENANCE EXHIBITIONS 294n.4; Giambattista Tiepolo 1998, 33, 37, Veil-Picard collection, France, until Fort Worth 1993, no. 8. 112, fig. 14; Pedrocco 2002, 219-20, about 1960; private collection, fig. 7I.2.K Switzerland; sold, Sotheby's, London, BIBLIOGRAPHY December n, 1985, lot 19, to Bob P. Conisbee, Levkoff, and Rand 1991, Habolt and Co., New York; sold 161—64, fig. 42; Brown 1993, 167—68, to the Los Angeles County Museum fig. 8; Gemin and Pedrocco 1993, of Art, 1986. 268, fig. io2b; Christiansen 1996, 292, THE STORY OF APOLLO AND PHAETHON 1719-20 fresco for the Palazzo Baglioni in is best known from Ovid's moving 1 Massanzago, near Padua. By contrast, in the Los interpretation from the Metamorphoses (1:750- Angeles composition Tiepolo presents the psy- 2:380). When aspersions were cast on the divine chologically taut moment in which Apollo vainly parentage of Phaethon—son of the mortal attempts to dissuade his son from his imprudent Clymene and the sun god, Apollo—his mother desire to drive the chariot. Father and son stand brought the young man to Apollo's heavenly at center, bathed in an aureole of light. Their palace to meet his father. After warmly embrac- gestures echo one another: Apollo raises his arm ing his son, Apollo granted Phaethon one wish, to ward off his son's entreaties while Phaethon and the young man impetuously asked to drive gestures urgently at the horses and—foreshad- the chariot of the sun. Apollo tried to dissuade owing later events—points to Scorpio in the Phaethon from this rash request, but—incapable zodiac behind him. Meanwhile, three horses of overcoming his son's steadfast insistence rear up at bottom right, barely restrained by the and rushed by the departure of the goddess of winged Hours. At the top of the canvas, Saturn, dawn—Apollo unwillingly assented. Apollo the god of time, rises, bearing his scythe in instructed his son carefully, but the steep path ominous anticipation of Phaethon's impending across the sky and the unmanageable horses doom. Tiepolo paid close attention to the clas- overwhelmed the young man, who quickly lost sical text, carefully representing such Ovidian control of the chariot and veered too close to details as the monumental marble column of the zodiac. Scorpio thrashed his tail in response Apollo's palace; the golden chariot, attended by to the heat, terrifying Phaethon, who dropped the Hours; and the personifications of the four the reins. The horses bolted wildly across the seasons at center right: Spring bearing a garland skies, scorching heaven and earth, until Zeus of flowers, Summer with wheat and a flaming threw a thunderbolt to regain control of the sun, torch, Autumn holding a crown of grape leaves, demolishing the chariot and sending Phaethon 2 and Winter as a bearded man huddled at rear. plunging to his death. The sketch at the Los Angeles County Artists depicting this myth were usually Museum of Art represents a frescoed ceiling for attracted to the dynamism of Phaethon's fall, a the Palazzo Archinto in Milan (fig. 4.1), destroyed subject Tiepolo himself had painted in an early by an American bombardment in August 1943. 33

CAT. NO. 4 34

FIGURE 4.1 Giambattista Tiepolo. Apollo andPhaethon, 1731. Fresco destroyed in World War II. Formerly Milan, Palazzo Archinto. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York. FIGURE 4.2 Giambattista Tiepolo. Oil sketch for The Triumph of the Arts and Sciences, ca. 1731. Oil on canvas. Lisbon, Museo Nacional de Arte Antiga. Photo: Jose Pessoa; Divisao de Documenta^ao Fotografica, Institute Portugues de Museus. APOLLO AND PHAETHON 35

FIGURE 4.3 Giambattista Tiepolo. Oil sketch for Perseus FIGURE 4.4 Giambattista Tiepolo. Juno Presiding over and Andromeda, ca. 1730. Oil on paper mounted on canvas. Fortune and Venus, 1731. Fresco destroyed in World War II. New York, Frick Collection, 18.1.114. Formerly Milan, Palazzo Archinto. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York. Carlo Archinto, a major early settecento Milanese Borromeo families. Others may relate to epithal- patron of science and the arts, commissioned amic poetry commissioned at the time of the the frescoes in 1731, probably at the instigation marriage, including Apollo and Phaethon, which of Archinto's librarian, Filippo Argelati. These draws on the genre's common association Milanese works were Tiepolo's first major of the bride with the sun.5 Tiepolo underscores ceiling projects outside the Veneto, at the cusp this connection by the unusual inclusion of of Tiepolo's soon-to-explode international sunflowers at bottom right, surely a reference to recognition.3 Clytie, transformed into a sunflower to follow The project comprises five frescoes, probably her beloved Apollo and thus a symbol of fidelity6 executed in two separate campaigns. The vast Despite his devotion to Ovid, Tiepolo pre- Triumph of the Arts and Sciences (fig. 4.2) dominated sents the narrative with creative invention the family's important library, while four smaller and remarkable ease and assurance. In contrast ceiling frescoes appeared in surrounding rooms: to the early Palazzo Sandi ceiling (see cat. no. i), Perseus and Andromeda (fig. 4.3), Juno Presiding over in which Tiepolo separated the principal scenes Fortune and Venus (fig. 4.4), Nobility, and Apollo around the edges of the composition, Apollo and 4 and Phaethon. While the main ceiling refers Phaethon represents an enormous step forward, primarily to the magnanimous artistic patronage interweaving the subnarratives into a sophis- of the Archinto family, the other works relate ticated spiraling composition. Imagined as to the marriage of Filippo Archinto to Giulia a ceiling painting, the di sotto in su composition Borromeo Grillo in April 1731. Some of these radically foreshortens all the figures, accentuating nuptial references are straightforward, such the rise of Phaethon to the heavens. Sharp con- as, in Juno, the presence of Hymen, the god of trasts of light and dark create a dramatic sense marriage, holding the arms of the Archinto and of sunlight by opposing the bright rings of light 36

FIGURE 4.5 Giambattista Tiepolo. Apollo andPhaethon, FIGURE 4.6 Giambattista Tiepolo. Apollo and Phaethon, ca. 1733-36. Oil on canvas. County Durham, England, Barnard ca. 1733-36, Oil on canvas. Vienna, Gemaldegalerie der Castle, The Bowes Museum. Akademie der bildenden Kiinste. that surround the protagonists with the rich, dark early career remains a hotly contested question. colors below (the double ground layer, reddish Around the time of the Palazzo Archinto browns and ocher, heightens this intensity of commission Tiepolo executed a number of other color). The light tonalities of the painting's cen- sketches on the theme of Apollo and Phaethon, ter band stand apart from the sinister shadows but their relationship to the LAC MA canvas and formed by the horses and the clouds, accentuating the ceiling itself remains unclear. Two beauti- the sense of foreboding. ful oil sketches from Barnard Castle and Vienna This painting follows the finished fresco (figs. 4.5—6) are easel paintings, with composi- quite closely a feature rarely exhibited in Tiepolo's tions in a rising S-curve, free of any di sotto in su sketches for ceiling frescoes (for example, cat. effects. The Vienna sketch, breezily painted nos. i and 8). For this reason most scholars have on an unusual blue-gray ground, depicts a slightly argued against it as a preliminary design, seeing later moment in the narrative, with Time taking the work as an unusually high-quality ricordo of Phaethon away from Apollo to the awaiting the ceiling, entirely by Tiepolo's hand.7 chariot. The Barnard Castle work, by contrast, How this painting relates to the other paint- bears a much closer connection to the actual ings and drawings of this subject from Tiepolo's ceiling, not only in its tonality but also in such APOLLO AND PHAETHON 37

FIGURE 4.7 Giambattista Tiepolo. Study for Apollo and Phaethon, ca. 1730. Pen and ink with brown wash on paper. London, The British Museum, 1917-5-12-2. Presented by Henry Oppenheimer. details as the chariot pushed by putti, the 3 For an interpretation of the ceilings and the overall grouping of the Seasons, the zodiac crossing the progression of the paintings, see especially Sohm 1984; auroral sky, and the position of father and son. and Levey 1986, 54-61. Beverly Louise Brown considers the Vienna pic- 4 Like the other smaller ceilings, Apollo and Phaethon ture a preliminary sketch executed after Tiepolo was surrounded by stuccos, which incorporated eight grisailles by Tiepolo, in this case presenting other accepted the commission but before he arrived stories from Apollo's life. in Milan, but other scholars disagree, considering 5 Sohm 1984, 71. both paintings later reworkings of the same 6 Sohm 1984, 70-71. Clytie also derives from Ovid's theme, with Christiansen dating them as late as Metamorphoses (4:169-270). 8 7 Beverly Louise Brown (1993, 167) and Richard Rand ca. 1733-36 Equally puzzling is a large drawing in Conisbee, Levkoff, and Rand 1991, 163, argue con- in the British Museum (fig. 4.7) that seems vincingly for the work as a ricordo. Keith Christiansen to come between the Vienna picture and the provides the most significant counterargument, asserting Archinto ceiling. The drawing retains the posi- that the uniform level of "style and character" of the tion of the rearing horse and chariot from the LAC MA sketch with the modelli in Lisbon and the New York makes it difficult to argue for this picture as a easel painting, but it adopts the J/ sotto in su per- ricordo (Christiansen 1996, 295^4). The Lisbon sketch, spective— only the earlier type that Tiepolo however, differs considerably from the final composition, had used for the Palazzo Sandi ceiling, with the and Tiepolo executed the Frick sketch on paper mounted scene arranged along a cornice line. aj> on canvas, two important distinctions from the LAC MA painting that make it difficult to see the three paintings as a unified group. 8 Antonio Morassi (1962, 3, 66) also considered the NOTES works preliminary sketches. Beverly Louise Brown (1993, 161-66) considers the Barnard Castle sketch a nineteenth-century pastiche but accepts the Vienna 1 Pedrocco 2002, 198. canvas as a preliminary sketch. For the most persuasive 2 Entry by Richard Rand in Conisbee, Levkoff, and Rand arguments for the paintings as later interpretations 1991, 161, 163. of the myth by Tiepolo, see Christiansen 1996, 292-9$. 8 3

$A Saint Rocco ca. 1730-3$ Oil on canvas 3 44 x 33.$ cm (i7 /s x 13/8 in.) The Samuel Courtauld Trust at the Courtauld Institute Gallery, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; inv. 171 PROVENANCE Courtauld Institute of Art, University BIBLIOGRAPHY Sold, Christie's, London, 1905, to Julius of London, 1978. Sack 1910, 99, 191; Morassi 1950, 209; Bohler, Munich; sold to Baron von Seilern 1959, 160, pi. CXXXIV; Stumm, Rauisch-Holzhausen, Hessen, EXHIBITIONS Morassi 1962, 20, fig. 163; Piovene and Germany, 1906; Count Zoubow, London 1960, no. 445. Pallucchini 1968, 96-97, fig. 77!!; Paris; sold to Count Antoine Seilern Seilern i97ia, 57; Braham 1981, 73-74, (1901-1978), London, 1952; by bequest fig. 108; Bradford and Braham 1989, to the Home House Trustees for the 25; Gemin and Pedrocco 1993, 306, 308-9, fig. 193; Pedrocco 2002, 230-31, fig. 103.9. 5B Saint Rocco ca. 1730-35 Oil on canvas 9 5 43 x 32 cm (i6 /i6 x i2 /s in.) San Marino, California, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens PROVENANCE EXHIBITIONS Probably James Smith Inglis (1852— None. 1907), New York; upon his death probably held in trust by Cottier and BIBLIOGRAPHY Co., New York; sold, Cottier and Co. Morassi 1950, 202-3, 206, fig. 9; sale, American Art Gallery, New York, Morassi 1962, 47, fig. 157; Piovene and March n, 1909, lot 78, to Henry E. Pallucchini 1968, 96-97, fig. 77n; Huntington, San Marino, California. Gemin and Pedrocco 1993, 306, 310, fig. 200; Pedrocco 2002, 230-31, fig. 103.16. sAINT ROCCO (CA. 1295-1327; ALSO CALLED with bread from a nearby bakery and healed his Saint Roch) relinquished his family fortune, wounds by licking them. After recovering he traveled from Montpellier, France, to Italy in returned to France, where he was — according the disguise of a pilgrim, and dedicated himself to some versions of his life—mistaken as a spy to curing the plague-stricken. Contracting the and thrown into prison unrecognized, and died. disease himself near Piacenza, Rocco withdrew Pilgrims and those suffering from the plague to the outlying forest, where a dog provided him commonly invoked Rocco, and many altars, 39

CAT. NO. $A 40

CAT. NO. 5B SAINT ROCCO 41

FIGURE $.1 Giambattista Tiepolo. Saint Rocco, 1730-35. FIGURE 5.2 Giambattista Tiepolo. Saint Rocco, 1730-3$. Oil on paper mounted on canvas. Philadelphia Museum Oil on canvas. Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, of Art, John G. Johnson Collection. gift of Sir J. S. Heron 1912, 1152. Photo: Ray Woodbury for AGNSW. churches, and confraternities were dedicated to landscape visible through the window at right. the saint throughout Europe. Exhausted and haggard, Rocco—now bearded, In the Courtauld canvas, a beardless Saint modestly clad, and significantly older—rests Rocco, with downturned head and closed eyes, his head and shoulder against the wall, barely sits facing the viewer. Tiepolo pulls the young able to open his eyes, prop up his staff, and clasp man to the front of the picture plane; the simple a piece of bread. Here Tiepolo reverses the gray wall, stone ledge, and dark shadows accen- relationship of light and dark, brightly lighting tuate the saint's monumental profile. Despite the composition from the right and shrouding his patched cloak, unkempt hair, and shabby the saint's face and torso in darkness. The boot, Saint Rocco bears clear traces of his cast- striking shadow formed on the wall increases his off wealth. Tiepolo paints his garments with distance from the viewer, locking the saint into radiant luxuriousness: a brightly lit apricot his enervated position. mantle covers a long, shimmering, vermilion In 1950, Antonio Morassi first identified a robe. The walking stick, loaf of bread, and scal- unified group of images by Tiepolo, all of similar loped shell pinned to his cloak all indicate he scale, depicting the same model in various is a pilgrim, but the saint rests from his peregri- 1 guises as Saint Rocco (figs. S.i-i). Subsequent nations, pulling back his robe to reveal a plague authors expanded this group of paintings, sore, highlighted with transparent red glaze, with Filippo Pedrocco recently counting twenty- tenderly observed by the dog, whose head and one as autograph.2 All scholars agree that the paw poke into the image at bottom right. works connect to the Confraternita di San Rocco By contrast, the Huntington's Saint Rocco in Venice. The church of San Rocco was long depicts an urban outcast instead of a pilgrim, 3 the site of exhibitions in the city and Tiepolo slumped before a stuccoed wall, a distant himself had a lengthy relationship with the 42