Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Faya Causey With technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES

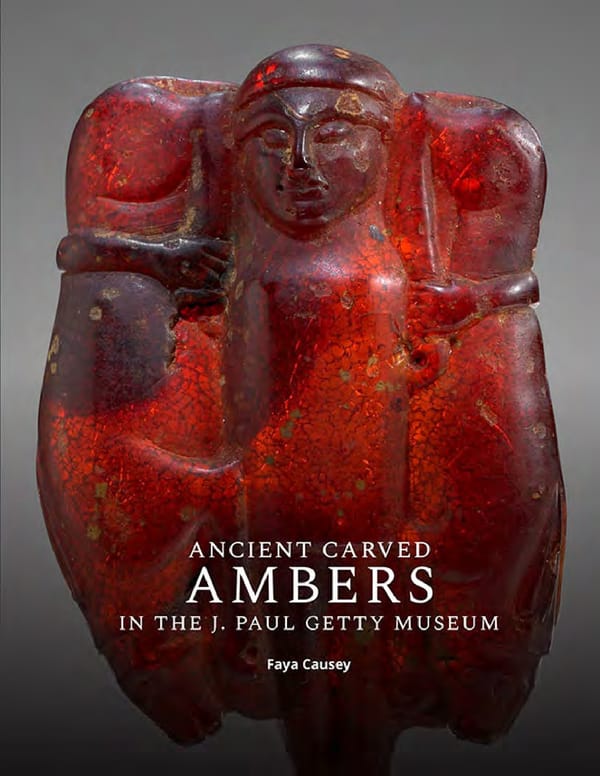

This catalogue was first published in 2012 at http: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data //museumcatalogues.getty.edu/amber. The present online version Names: Causey, Faya, author. | Maish, Jeffrey, contributor. | was migrated in 2019 to https://www.getty.edu/publications Khanjian, Herant, contributor. | Schilling, Michael (Michael Roy), /ambers; it features zoomable high-resolution photography; free contributor. | J. Paul Getty Museum, issuing body. PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads; and JPG downloads of the Title: Ancient carved ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum / Faya catalogue images. Causey ; with technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, © 2012, 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust and Michael Schilling. Description: Los Angeles : The J. Paul Getty Museum, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “This catalogue provides a general introduction to amber in the ancient world Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a followed by detailed catalogue entries for fifty-six Etruscan, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a Greek, and Italic carved ambers from the J. Paul Getty Museum. copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4 The volume concludes with technical notes about scientific .0/. Figures 3, 9–17, 22–24, 28, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 51, and 54 are investigations of these objects and Baltic amber”—Provided by reproduced with the permission of the rights holders publisher. acknowledged in captions and are expressly excluded from the CC Identifiers: LCCN 2019016671 (print) | LCCN 2019981057 (ebook) | BY license covering the rest of this publication. These images may ISBN 9781606066348 (paperback) | ISBN 9781606066355 (epub) not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or manipulated without | ISBN 9781606060513 (ebook other) consent from the owners, who reserve all rights. Subjects: LCSH: J. Paul Getty Museum—Catalogs. | Amber art objects—Catalogs. | Art objects, Ancient—Catalogs. | Art First edition 2012 objects, Etruscan—Catalogs. | Art objects—California—Los Paperback and ebook editions 2019 Angeles—Catalogs. | LCGFT: Collection catalogs. https://www.github.com/gettypubs/ambers Classification: LCC NK6000 .J3 2019 (print) | LCC NK6000 (ebook) | DDC 709.0109794/94—dc23 Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019016671 Getty Publications LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019981057 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90040-1682 Front cover: Pendant: Divinity Holding Hares (detail, 77.AO.82, cat. www.getty.edu/publications no. 4). First edition: Every effort has been made to contact the owners and Marina Belozerskaya and Ruth Evans Lane, Project Editors photographers of objects reproduced here whose names do not Brenda Podemski and Roger Howard,Software Architects appear in the captions. Anyone having further information Elizabeth Zozom and Elizabeth Kahn, Production concerning copyright holders is asked to contact Getty Publications Kurt Hauser, Cover Design so this information can be included in future printings. 2019 editions: URLs cited throughout this catalogue were accessed prior to first Zoe Goldman,Project Editor publication in 2012; during preparation of the present editions in Greg Albers, Digital Manager 2019, some electronic content was found to be no longer available. Maribel Hidalgo Urbaneja, Digital Assistant Where URLs are no longer valid, the author’s original citations have Suzanne Watson,Production been retained, but hyperlinks have been disabled in the online and ebook editions. Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London

Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Amber and the Ancient World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 Jewelry: Never Just Jewelry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Amber Magic? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 What Is Amber? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Where Is Amber Found? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 The Properties of Amber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 Ancient Names for Amber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23 Color and Other Optical Characteristics: Ancient Perception and Reception . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 Ancient Literary Sources on the Origins of Amber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 Amber and Forgery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37 The Ancient Transport of Amber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40 Literary Sources on the Use of Amber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 Amber Medicine, Amber Amulets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47 The Bronze Age . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 Early Iron Age and the Orientalizing Period . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 The Archaic and Afterward . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67 The Working of Amber: Ancient Evidence and Modern Analysis . . . . . . . . . . 78 The Production of Ancient Figured Amber Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87 Catalogue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91 Orientalizing Group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92 1. Pendant: Female Holding a Child (Kourotrophos) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

2. Pendant: Female Holding a Child (Kourotrophos) with Bird . . . . . . . . . 102 3. Pendant: Addorsed Females . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108 4. Pendant: Divinity Holding Hares . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112 5. Pendant: Lion with Swan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122 6. Pendant: Paired Lions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126 Ship with Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129 7. Pendant: Ship with Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130 Korai . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136 8. Pendant: Standing Female Figure (Kore) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 9. Pendant: Head Fragment from a Standing Female Figure (Kore) . . . . 145 Human Heads . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147 10. Pendant: Head of a Female Divinity or Sphinx . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155 11. Pendant: Head of a Female Divinity or Sphinx . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158 12. Pendant: Satyr Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162 13. Pendant: Satyr Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167 14. Pendant: Female Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170 15. Pendant: Winged Female Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173 16. Pendant: Winged Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177 17. Pendant: Female Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179 18. Pendant: Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181 19. Pendant: Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183 20. Pendant: Female Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185 21. Pendant: Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186 22. Pendant: Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 188 23. Pendant: Winged Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190 24. Pendant: Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192 25. Pendant: Female Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194 26. Pendant: Female Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196 Animals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198

27. Roundel: Animal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199 28. Plaque: Addorsed Sphinxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203 29. Pendant: Hippocamp . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 206 30. Pendant: Cowrie Shell / Hare . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 210 31. Pendant: Lion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214 32. Pendant: Female Animal (Lioness?) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218 Lions’ Heads . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 220 33. Pendant: Lion’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223 34. Spout or Finial: Lion’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225 35. Pendant: Lion’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227 36. Pendant: Lion’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229 Boars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231 37. Pendant: Foreparts of a Recumbent Boar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232 38. Plaque: Addorsed Lions’ Heads with Boar in Relief . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235 Rams’ Heads . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 238 39. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243 40. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245 41. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246 42. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247 43. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 248 44. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249 45. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 250 46. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252 47. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253 48. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254 49. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255 50. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 256 51. Pendant: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257 52. Finial(?): Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 258 53. Spout or Finial: Ram’s Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

Other Animal Heads . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 260 54. Pendant: Bovine Head . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261 55. Pendant: Horse’s Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264 56. Pendant: Asinine Head in Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 268 Forgery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270 57. Statuette: Seated Divinity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271 Technical Essay: Analysis of Selected Ambers from the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum—Jeff Maish,Herant Khanjian,and Michael R. Schilling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272 Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284 Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 286 About the Authors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 297

Introduction

Amber and the Ancient World The J. Paul Getty Museum collection of amber antiquities The ambers were acquired by their donors on the was formed between 1971 and 1984. Apart from the international art market. The loss of any artifact’s context RomanHead of Medusa(figure 1), which Mr. Getty is immeasurable, and any attempt to discuss ambers acquired as part of a larger purchase of antiquities in without their original context is, to borrow an analogy 1971, all the other ancient amber objects were acquired as from Thorkild Jacobsen, “not unlike entering the world of gifts. The collection is made up primarily of pre-Roman poetry.” Poetry plays a part in locating the cultural material, but also includes a small number of Roman- ambients in which the ambers of this catalogue once period carvings, of which the Head of Medusa is the most performed. In addition to ancient literary sources, the important. The pre-Roman material includes a variety of work here is examined via a large interdisciplinary jewelry elements that date from the seventh to the fourth toolkit, including art history, archaeology, philology, centuries B.C.: fifty-six figured works and approximately pharmacology, anthropology, ethnology, and the history of twelve hundred nonfigured beads, fibulae, and pendants. medicine, religion, and magic. This volume examines the fifty-six objects of pre-Roman At a critical moment in writing this introduction, I read date representing humans, animals, and fantastic two of Roger Moorey’s final contributions, his 2001 creatures, plus a modern imitation. The Getty’s Schweich Lectures, published as Idols of the People: nonfigured pre-Roman objects and the Roman works are Miniature Images of Clay in the Ancient Near East (2003), not included in this catalogue. and his Catalogue of the Ancient Near Eastern Terracottas in the Ashmolean (2004). Both were important to the final shaping of my text. (It is from the latter publication that I borrowed Jacobsen’s quotation.) Certain of Moorey’s observations played critical roles; among them is his cautionary note in the Catalogue: “Even if it may be possible to identify who or what is represented, whether it be natural or supernatural, that does not in itself resolve the question of what activity the terracotta was involved in.”1 Indeed, in what “activity” were these carved ambers involved? This catalogue attempts to address this question. Keeping in mind the challenges presented when working with decontextualized artifacts, I make comparisons to scientifically excavated parallels, to documented works in museums, and, with extra care, to unprovenanced material in other collections, public and private. The evidence suggests that amber was dedicated primarily to female divinities, and that most pre-Roman Figure 1 Head of Medusa, Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D. Amber, H: 5.8 cm amber objects were buried with women and children. (23⁄10 in.), W: 5.8 cm (23⁄10 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 71.AO.355. Individually and as a whole, the Getty Museum’s amber objects are important witnesses to the larger social picture of the people who valued the material.2 2

My interest was first sparked by the peculiar nature of the of other contemporary visual arts media. There are many carved amber on display in the British Museum and by reasons for this lag, including the nature of the material itself. Donald Strong’s masterful 1966 catalogue of the material.3 Only a small number of carved amber objects are on display in Strong duly noted the magical aspects of the subjects of public collections; relatively few are published or even Italian Iron Age ambers, and I took as a challenge one illustrated; and too few come from controlled contexts. Many comment: “Many of the more enigmatic subjects among important works are in private collections and remain these carvings probably have a meaning that is no longer unstudied. Moreover, under some burial conditions, and clear to us.”4 because of its chemical and physical structure, amber often suffers over time. Poorly conserved pieces are friable, difficult to NOTES conserve and sometimes even to study; they can be handled only with great care and therefore are notoriously difficult to 1. Moorey 2004, p. 9. photograph, illustrate, or display. Much more remains to be learned about amber objects from a uniform application of 2. White 1992, p. 560: “We have seen in the ethnographic record scientific techniques, such as neutron activation analysis, that material forms of representation are frequently about infrared spectrometry, isotope C12/C13 determination, and political authority and social distinctions. Personal ornaments, pyrolysis mass spectrometry (PYMS), as recent research has constructed of the rare, the sacred, the exotic, or the labor/skill demonstrated. For the various methods of analysis, see the intensive, are universally employed, indeed essential to addendumto this catalogue by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and distinguish people and peoples from each other.” White’s work Michael Schilling; also Barfod 2005; Langenheim 2003; Serpico on Paleolithic technology, the origins of material representation 2000; Ross 1998; and Barfod 1996. C. W. Beck’s lifetime of work in Europe, and the aesthetics of Paleolithic adornment have on amber is indicated in the bibliographies of these informed this study more than any specific reference might publications. indicate. Throughout his work, White underlines the variety, To date, only a very small percentage of pre-Roman ancient richness, and interpretive complexity of the known corpus of objects have been analyzed. Several key projects specifically prehistoric representations. It is through his work that I began related to the study of amber in pre-Roman Italy were to understand the nonverbal aspects of adornment and to completed in recent years, including the cataloguing of amber consider systems of personal ornamentation. See R. White, in the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris (D’Ercole 2008), and that in “Systems of Personal Ornamentation in the Early Upper the National Museum, Belgrade, and in Serbia and Montenegro Paleolithic: Methodological Challenges and New Observations,” (Palavestra and Krstić 2006). In addition, two recent exhibitions in Rethinking the Human Revolution: New Behavioural and of amber from the Italian peninsula, the 2007 Ambre: Biological Perspectives on the Origin and Dispersal of Modern Humans, ed. P. Mellars et al. (Cambridge, 2007), pp. 287–302; Trasparenze dall’antico, in Naples, and the 2005 Magie d’ambra: and R. White, Prehistoric Art: The Symbolic Journey of Humankind Amuleti et gioielli della Basilicata antica, in Potenza, have added (New York, 2003), p. 58, where he cites the innovative G. H. much to the picture of amber consumption, especially for pre- Luquet, L’art et la religion des hommes fossiles (Paris, 1926). In the Roman Italy. In 2002, Michael Schilling and Jeffrey Maish of the 2007 article, White publishes the earliest known amber pendant Getty Conservation Institute identified thirty-five ambers in the (the amber is almost certainly from Pyrenean foreland sources), Getty collection as Baltic amber (see the addendum to this from the Archaic Aurignacian level 4c6 at Isturitz, France. catalogue). 3. The watershed British Museum catalogue of carved amber by 4. Strong 1966, p. 11. Strong also comments: “Etruscan necklaces Strong was published in 1966 (Strong 1966). Since that time, include a wide range of amulets of local and foreign derivation there has been considerable research on amber in the ancient and the whole series of ‘Italic’ carvings consist largely of world and related subjects, and a significant number of amber- pendants worn in life as charms and in death with some specific studies have been published during the last several apotropaic purpose. The big necklaces combined several well- years. These range in type from exhibition and collection known symbols of fertility, among them the ram’s head, the catalogues, excavation reports, and in-depth studies of frog, and the cowrie shell. The bulla which is common in amber individual works to broader sociocultural assessments. Still, was one of the best-known forms of amulet in ancient Italy.” many finds and investigations (including excavation reports) (For the bulla, see n. 152.) await publication, and the study of amber objects is behind that Amber and the Ancient World 3

Jewelry: Never Just Jewelry The fifty-six pre-Roman amber objects in this catalogue actions often lack, or carry messages too dangerous or can be considered collectively as jewelry. However, in the controversial to put into words. In life, in funeral rituals, ancient world, as now, jewelry was never just jewelry. and in the grave, the decoration of the body with amber Today, throughout the world, jewelers, artisans, and jewelry and other body ornaments would have had a merchants make or sell religious symbols, good-luck social function, solidifying a group’s belief systems and charms, evil eyes, birthstones, tiaras, mourning pins, reiterating ideas about the afterworld. Perhaps more than wedding rings, and wristwatches. Jewelry can signal any other aspect of the archaeological record, body allegiance to another person, provide guidance, serve a ornamentation is a point of access into the social world of talismanic function, ward away danger, or link the the past. Ethnographers see body ornamentation as wearer to a system of orientation—as does a watch set to affirming the social construct and structure and, when Greenwich Mean Time—or to ritual observances. worn by the political elite, as guaranteeing group beliefs. Birthstones and zodiacal images can connect wearers to Interpretations of the meanings of body ornamentation their planets and astrological signs. Certain items of imagery must consider how “artistic” languages work to jewelry serve as official insignia: for example, the crown create expressive effects that are dependent upon the jewels of a sovereign or the ring of the Pontifex Maximus. setting. A cross or other religious symbol can demonstrate faith or an aspect of belief. Not only goldsmiths make jewelry; so Jewelry is made to be worn; it is often bestowed or given also do healers and other practitioners with varying levels as a gift at significant threshold dates; and it is regularly of skill. In the West today, most jewelry is made for the imbued with or accrues sentimental or status value living; in other parts of the world, objects of adornment because of the giver or a previous wearer or donor. In may be particular to the rituals of death and intended as antiquity, jewelry also was given to the gods (figure 2). permanent accompaniments for the deceased’s remains. Dedications might be made at the transition to Much jewelry, especially if figured, belongs to a womanhood, following a successful birth, or in phenomenology of images, and it functions in ritual ways. thanksgiving. Jewelry of gold, amber, ivory, or other It is part of a social flow of information and can establish, precious materials might be placed on cult statues to form modify, and comment on major social categories, such as part of the statue’s kosmos, or embellishment. In notable age, sex, and status, since it has value, carries meaning, cases, such embellishment was later renewed and the old and suggests communication within groups, regions, and material buried as deposits in sanctuaries.5 often larger geographical areas. Underlying my discussion of ancient carved amber is the belief that jewelry (adornment and body ornamentation) is value-laden and that its form and material qualities (the ancient use of rare and exotic materials reflects labor, skill, and knowledge-intensive production) are powerful indicators of social identity. Permanent ornaments can endure beyond one human life and can connect their wearers to ancestors, thus playing a crucial role in social continuity—especially when we consider that such objects are imbued with an optical authority that words and 4

object of adornment, too, are problematic. One of the more accurate terms, amulet (figure 3), is also loaded, as it is situated on a much-discussed crossroads among magic, medicine, ritual, and religion. Amulet is a modern word, derived from the Latin amuletum, used to describe a powerful or protective personal object worn or carried on the person. “Because of its shape, the material from which it is made, or even just its color,” an amulet “is believed to endow its wearer by magical means with certain powers and capabilities.”7 Figure 2 Ring dedicated to Hera, Greek, ca. 575 B.C. Gilded silver, Diam. (outer): 2.2 cm (7⁄8 in.), Diam. (inner): 1.8 cm (11⁄16 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum,85.AM.264. Jewelry is one of the most powerful and pervasive forms in which humans construct and represent beliefs, values, and social identity. When made by artists or artisans of the highest skill, lifelike images can carry magical and dynamic religious properties and can even be highly charged ritual objects in their own right. Tiny carved amber images buried with people considered to be members of religious-political elites may well have played such a role. Figure 3 Amber necklaces and gold ornaments from the young girl’s Tomb The nature and role of amber-workers—jewelers, 102, Braida di Serra di Vaglio, Italy, ca. 500 B.C. The sphinx pendant, the pharmacists, priests, “wise women,” and magicians—are largest amber pendant, has H: 4.6 cm (13⁄4 in.), L: 8.3 cm (31⁄4 in.), W: 1.5 cm (5⁄8 in.). Approximate total length of strings of amber: 240 cm (941⁄2 in.). critical to reading body ornaments. Not only the materials Potenza, Museo Archeologico Nazionale “Dinu Adamesteanu.” By permission and subjects, but also the technology of jewelry-making, of il Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali—Direzione Regionale per i were integral to its effect. If the materials were precious Beni Culturali e Paesaggistici della Basilicata—Soprintendenza per i Beni and the making mythic or magical, the results were Archeologici della Basilicata / IKONA. appropriate for the elite, including the gods. The concept NOTES of “maker” also includes supernatural entities, such as magician-gods and other mythic artisans. In the Greek- 5. Paraphrased from D. Williams and J. Ogden, Greek Gold: Jewelry speaking world, the Iliad describes Hephaistos at work in of the Classical World (London, 1994), pp. 31–32. his marine grotto, making arms, armor, and jewelry: elegant brooches, pins, bracelets, and necklaces. The god 6. Many figured ambers might have been brought to an ancient crafted Harmonia’s necklace and Pandora’s crown. Greek-speaking viewer’s mind by the words daidalon, kosmos, Daidalos put his hand to all sorts of creations and gave his andagalma,specifically the daidalon worn by Odysseus: a gold name to one of the most famous of all Greek objects of brooch animated with the image of a hound holding a dappled adornment: Odysseus’s brooch.6 fawn in its forepaws, the fawn struggling to flee (Odyssey 19.225–31). Sarah Morris first brought this example to my This said, there is a problem with the language. The attention. See S. P. Morris, Daidalos and the Origins of Greek Art modern wordjewelryis, in the end, limiting and fails to (Princeton, 1992), esp. pp. 27–29. See also Steiner 2001, pp. encompass the full significance of the carved ambers. The 20–21; and F. Frontisi-Ducroux, Dédale: Mythologie de l’artisan en termsornamentandbody ornamentation,adornmentand Grèce ancienne (Paris, 2000). Jewelry 5

What M. J. Bennett (Langdon 1993, pp. 78–80) writes about Galen, for example, sanctions the use of incantations by Greek Geometric plate fibulae might be applicable to other doctors (Dickie 2001, p. 25, and passim). contemporary and later precious figured ornaments in the Other works invaluable for framing this discussion of amulets Greek-speaking world. Objects with complex imagery might and amber areThesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum, vol. 3, reflect “the ordering of the world (kosmos).… Considering that s.v. “magic rituals”; R. Gordon, “Innovation and Authority in kosmos meant ‘the universe,’ ‘order,’ ‘good behavior,’ as well Graeco-Egyptian Magic,” in Kykeon: Studies in Honour of H. S. as ‘a piece of jewelry,’ the fibula was not a mere fashion Versnel, ed. H. F. J. Horstmannshoff et al. (Leiden, Boston, and accessory, but rather a sophisticated ontological statement.” G. Cologne, 2002), pp. 69–112; S. Marchesini, “Magie in Etrurien in F. Pinney, Figures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece orientalisierender Zeit,” in Prayon and Röllig 2000, pp. 305–13; (Chicago, 2002), p. 53, with reference to Hesiod’s Theogony W. Rollig, “Aspekte zum Thema ‘Mythologie und Religion,’” in 581–84, writes: “The vocabulary of kosmos makes ample use of Prayon and Röllig 2000, pp. 302–4; Oxford Companion to words for splendor and light: lampein, phaeinos, aglaos, Classical Civilization, ed. S. Hornblower and A. Spawforth sigaloeis.” The point is glamour in the form of radiance, light (Oxford and New York, 1998), s.v. “magic” (H. S. Versnel), p. emanating from shimmering cloth and gleaming metals. 441; P. Schäfer and H. G. Kippenberg, Envisioning Magic: A Agalmaoccupied distinct but related semantic areas in Greek, Princeton Seminar and Symposium (Princeton, 1997); Meyer and asKeesling 2003, p. 10, describes: “It could designate any Mirecki 1995; Pinch 1994, pp. 104–19; Andrews 1994; Wilkinson pleasing ornament, or a pleasing ornament dedicated to the 1994; Ritner 1993; Faraone 1992; Faraone 1991; and esp. gods. In the fifth century, Herodotus used agalma to refer Kotansky 1991; Gager 1992, pp. 218–42; H. Philipp, Mira et specifically to statues, the agalmata par excellence displayed in magica: Gemmen im Ägyptischen Museum der Staatlichen the sanctuaries of his time.” M. C. Stieber, The Poetics of Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin-Charlottenburg (Mainz, 1986); Appearance in the Attic Korai (Austin, TX, 2004), is illuminating as Bonner 1950; and S. Seligman, Die magischen Heil- und she probes agalma for the sculptures and their accoutrements Schutzmittel aus der unbelebten Natur mit besonderer in her discussion of the kore as an agalma for the goddess and Berücksichtung der Mittel gegen den bösen Blick: Ein Geschichte the korai as agalmata in and of themselves. She reminds us des Amulettwesens (Stuttgart, 1927). In Egypt, an amulet could that the term is used of real women in literature (Helen of Troy at the very least, as Andrews 1994, p. 6, summarizes, and Iphigenia in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon 7.41 and 208, afford some kind of magical protection, a concept confirmed respectively). by the fact that three of the four Egyptian words translate as 7. Andrews 1994, p. 6. The literature on amulets, amuletic “amulet,” namely mkt (meket), nht (nehet) and s3 (sa) come practice, magic, and ritual practice in the ancient world is vast. primarily from verbs meaning “to guard” or “to protect.” The The termmagicis used here in its broadest and most positive fourth, wd3 (wedja), has the same sound as the word sense. Although M. Dickie and others argue that magic did not meaning “well-being.” For the ancient Egyptian, amulets and exist as a separate category of thought in Greece before the jewelry [that] incorporate amuletic forms were an essential fifth century B.C., practices later subsumed under the term did, adornment, especially as part of the funerary equipment for especially the use of amulets. The use of amulets implies a the dead, but also in the costume of the living. Moreover, continuing relationship between the object and the wearer, many of the amulets and pieces of amuletic jewelry worn in continuing enactment, and the role of at least one kind of life for their magical properties could be taken to the tomb practitioner. Dickie 2001, p. 130, concludes that the existence for use in the life after death. Funerary amulets, however, and wide use of amulets in Rome by the Late Republic “leads and prescribed funerary jewelry which was purely amuletic in us back into a hidden world of experts in the rituals of the function, were made expressly for setting on the wrapped manufacture and application of amulets, not to speak of those mummy on the day of the burial to provide aid and who sold them.” Pliny uses three words to describe amber protection on the fraught journey to the Other world and items used in medicine, protection, and healing: amuletum, ease in the Afterlife. monile (for a necklace), and alligatum, when citing Callistratus. In the ancient Near East, the great variety of human problems Greek terms for amulet include periamma and periapta. handled by recourse to amulets is already well documented in Following Kotansky 1991, n. 5, I use amulet to encompass the the Early Dynastic period. See B. L. Goff, Symbols of Prehistoric modern English talisman and also phylaktērion. The Greek Mesopotamia(New Haven and London, 1963), esp. chap. 9, recipes in the Papyri Graecae Magicae use the latter term. “The Role of Amulets in Mesopotamian Ritual Texts,” pp. In early Greece, as elsewhere earlier in the Mediterranean 162–211. The role of magic as described in Assyro-Babylonian world, an amulet was applied in conjunction with an elite literature is relevant: magic was prescribed and overtly incantation, as Kotansky (ibid.) describes. Incantations practiced for the benefit of king, court, and important required the participation of skilled practitioners and receptive individuals; it was not marginal and clandestine; and only participants. Socrates, in Plato’s Republic, lists amulets and noxious witchcraft was forbidden and prosecuted. See E. incantations as among the techniques used to heal the sick, a Reiner, Astral Magic in Babylonia (Chicago, 1995). tradition that continued at least into the Late Antique period. 6 INTRODUCTION

Keeping in mind the cultural variants of death and burial rituals in the places and periods under consideration here, there may have been a considerable lag between death and the readying of the corpse, including cremation, excarnation, or other preparations before burial rituals. The production of sumptuary and ritualistic objects suggests the existence of specialists (religious-ceremonial or political-ceremonial) who themselves may have used insignia associated with their positions. Jewelry 7

Amber Magic? Whilemagicis probably the one word broad enough to of wear (figure 4). Unfortunately, we can only speculate as describe the ancient use of amulets, the modern public to whether the ambers were actually possessions of the finds the term difficult. As H. S. Versnel puts it, “One people with whom they were buried, how the objects problem is that you cannot talk about magic without were acquired, and in which cultic or other activity they using the term magic.”8 played a part. There is no written source until Pliny the But even if it were possible to draw precise lines of Elder, around A.D. 79, to tell us how amber was used in life (in a religious, medical, magical, or other context).13 demarcation between the ancient use of amber for Only a few fragments of information from early Christian adornment and its role in healing, between its reputation sources add to the Roman picture. All evidence before for warding off danger and its connection to certain Pliny is archaeological and extrapolated from earlier divinities and cults, such categorizations would run sources—from Egypt, the Aegean, the ancient Near East, counter to an understanding of amber in its wider and northern Europe. In Egypt, and to a lesser extent in context. Amber’s beauty and rarity were evident to an the ancient Near East, much more is known about how ancient observer, but its magnetic properties; distinctive, amuletic jewelry was produced, and by whom and for glowing, sunlike color and liquid appearance; inclusions whom it was produced. In both regions, we find instances and luster; and exotic origins were mysterious and awe- of amulets specifically designed for funerary use and of inspiring. Amber’s fascination and associative value previously owned amulets continuing their usefulness in prompted a wide range of overlapping uses.9 Pliny the Elder, for instance, put together an impressive list of uses the tomb. for amber, including as a medicine for throat problems and as a charm for protecting babies.10 Diodorus Siculus noted amber’s role in mourning rituals, and Pausanias guided visitors to an amber statue of Augustus at Olympia. The main sources of amber in antiquity were at the edges of the known world, and those distant lands generated further rich lore. Myths and realities of amber’s nature and power influenced the desire to acquire it. As the historian Joan Evans has observed, “Rarity, strangeness, and beauty have in them an inexplicable element and the inexplicable is always potentially magical.”11 Beliefs about amber’s mysterious origins and unique physical and optical properties affected the ways it was used in antiquity and the forms and subjects into which it was carved.12 Excavations during the last half century, especially in Italy, have greatly improved our understanding of how amber functioned in funerary contexts. The emerging Figure 4 Female Head in Profile pendant, Italic, 500–480 B.C. Amber, H: 4.4 picture is also enhancing our understanding of how cm (17⁄10 in.), W: 3.8 cm (11⁄2 in.), D: 1.6 cm (3⁄5 in). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty amber objects were used before their burial. A number of Museum, 77.AO.81.30. Gift of Gordon McLendon. See cat. no. 25. amber pendants, including the Getty objects, show signs 8

We might also ask how amber pendants in the form of into the world of the living could serve a similar function age-old subjects (goddesses [figure 5], animals, or solar in smoothing the transition into the afterworld, or world and lunar symbols) relate to older traditions. In the of the dead. Many images allude to a journey (figure 6) ancient Near East, Kim Benzel reminds us, symbolic that the deceased’s shade, or soul, takes after death, and jewelry pendants signified emblematic forms of major these pieces are difficult to see as intended for the living: deities from as early as the third millennium B.C.: these must have been gifts or commissions specifically for the dead. The ambers that show wear do not indicate who Symbols of divinities have a long tradition of used them. While there is no direct evidence as to representation in various media throughout the whether the amulets found in burials were owned by the ancient Near East. They were certainly meant to be deceased during their lives, it is tempting to assume that apotropaic, but likely had far greater efficacy than the this could have been the case. Were they purchases, part purely protective. An emblem was considered one of a dowry, heirlooms, or other kinds of gifts? Ambers mode of presencing a deity.… The power embodied in were made, at some point, for someone, whether bought [such] ornaments thus would have been analogous to on the open market or commissioned to order. Inscribed the power embedded in a cult statue—which is Greek magical amulets (lamellae) “that had been perhaps why in the later religions, along with idol commissioned for specific purposes (or most feared worship, jewels were banned.14 dangers) came to represent for their wearer a multivalent protection, a sine qua non for every activity in life. And in the face of the liminal dangers of the afterlife passage … this same amulet that had come to protect all aspects of life would now be considered crucial in death, the apotropaic token of the soul.”16 Figure 6 Ship with Figures pendant, Etruscan, 600–575 B.C. Amber, L: 12 cm (47⁄10 in.), W: 3.5 cm (13⁄8 in.), D: 1 cm (3⁄10 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 76.AO.76. Gift of Gordon McLendon. See cat. no. 7. The wear on many objects is undeniable. Some amber pendants are both worn and “old-fashioned” for the context in which they were found, and they cause us to remember that in antiquity there was a well-established tradition of gift giving during life and at the grave.17 Figure 5 Addorsed Females pendant, Etruscan, 600–550 B.C. Amber, H: 4.0 cm (13⁄5 in.), W: 10.2 cm (4 in.), D: 1.3 cm (1⁄2 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Figured ambers, including those in the Getty collection, Museum, 77.AO.81.1. Gift of Gordon McLendon. See cat. no. 3. may have been worn regularly in life for permanent protection or benefit; others, on a temporary basis or in The subjects of the Getty pre-Roman figured ambers vary, crises, such as childbirth, illness, or a dangerous journey. but without exception, they incorporate a protective as Others may have been grave gifts or offerings to well as a fertility or regenerative aspect.15 It is easy to see divinities, perhaps to propitiate underworld deities. In that the same amulet that had helped to ensure safe entry Amber Magic? 9

some cases, deceased girls may have been adorned as incorporate elements relating, for instance, to Dionysos or brides—a common aspect of funerary ritual. Artemis, but as such, they occupy a hazy territory between identifiable religious practices and what Einar How these objects might have functioned in reference to Thomassen calls “the appropriation of ritual power for clanship or other social identities, during either life or the personal ends.”18 The use of these amulets may have been rituals surrounding death, should also be considered. dictated to some extent by skilled practitioners, but it is Among certain populations, there might have been a likely that the original, specific use of a protective amulet generally accepted role for amber, in the range of subjects often would have eroded into a more generalized into which it was formed and/or the objects it portafortuna, or good-luck, role over time.19 The generally embellished. Some subjects might have been pertinent to feared evil eye might have been warded off with any clans or larger communities, in the way that shield amber amulet.20 emblazons might be. Some imagery might have been special to family groups, who may have traced their Worked amber and amber jewelry were well in evidence origins, names, or even good fortune to a particular deity, in northern Europe from the fourth millennium B.C. animal, totem, or myth. If an elite person whose family’s onward. The earliest evidence for worked amber in Italy founder was a divinity or Homeric hero was buried with a is from the Bronze Age. We do not know where the amber ring with an engraved gem representing, say, Herakles found in graves dating to circa 1500 B.C. in Basilicata (figure 7), Odysseus, or Athena, might the same have been (near Melfi and Matera) was carved. In the later Bronze done with figured ambers? Age, Adriatic Frattesina, a typical emporium of the protohistoric era, was a place of manufacture. Already by this time, variety in style, subject, technique, and function was evident. Some of these early ambers are the work of highly skilled artisans; others are rudimentary in manufacture and indicate work by other kinds of amber- workers/amulet-makers, perhaps even priestesses, physicians, or “wise women.” It is tempting to think of multiple ritual specialists involved in amber-working and amuletmaking, though perhaps in not so pronounced a fashion as in contemporary Egypt—although there is evidence for widespread amuletic usage in Italy even into modern times. We might well envision a scenario that includes simple gem cutters, sculptors, multiple ritual specialists—from healers to hacks—those with fixed locations in urban settings, and itinerants. Such a variety of practitioners offering objects and ritual expertise is likely, especially for amulets in a material as inherently magical as amber.21 NOTES 8. Reference from E. Thomassen, “Is Magic a Subclass of Ritual?” in Jordan et al. 1999, pp. 55–66. Figure 7 Engraved Scarab with Nike Crowning Herakles, Etruscan, 400–380 9. Strong 1966, pp. 10–11, considers the amuletic and the magical B.C. Banded agate, H: 1.8 cm (3⁄4 in.), W: 1.4 cm (9⁄16 in.), D: 0.9 cm (3⁄8 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AN.123. aspects of amber separately from its medical uses. He distinguishes between early Greek and later (presumably Classical) Greek attitudes: “In early Greece the amuletic values The extent to which some of these ornament-amulets had of amber seem to have been recognized.… But in the Greek a role in established cult or folk religion is difficult to world generally the principal attraction of amber was its ascertain, but it should not be either exaggerated or decorative qualities.” Strong also differentiates Italic Iron Age denied. The diversity of subjects that appear in figured usage from the Greek: in that period, the “amber carvings … amber over time suggests that the material was used underline the magical aspects of the use of amber.” within many different symbol systems, but always for its Waarsenburg 1995, p. 456, successfully undertakes a religious protective or regenerative aspects. Some pieces do interpretation in his study of the seventh-century B.C. Tomb VI 10 INTRODUCTION

at Satricum, countering the “viewpoint that Oriental or n. 194 for further discussion of ducks in amber.) Such objects Orientalising figurative amulets had only a very generic support the hypothesis that amber was traded with the south apotropaic function in Italy … and [that] they would not have in both finished and unfinished forms. H. Hughes-Brock, been understood by the native population. Related to this “Mycenaean Beads: Gender and Social Contexts,” Oxford viewpoint is an explicit reluctance against any interpretation Journal of Archaeology 18, no. 3 (August 1999): 293, suggests, which takes nonmaterial, sc. religious, aspects into account. “Some imports probably arrived with the specialist processes Even the symbol of the nude female is frequently denied a already completed nearer the source, e.g., preliminary removal specific meaning.” D’Ercole 1995, p. 268, n. 19, suggests that of the crust of Baltic amber.” Why not finished objects? beliefs surrounding amber, other than fashion or taste, might 13. S. Eitrem, Opferritus und Voropfer der Griechen und Röme (1915; explain the long-continuing repetition of subjects among repr., Hildesheim and New York, 1977), p. 194, discusses the certain groups of figured ambers. Mastrocinque 1991, p. 78, n. amuletic virtues of amber in Rome. 247, notes the supranormal aspects of figured amber, drawing attention to the relationship of the subject and the animating, 14. K. Benzel, in Beyond Babylon 2008, p. 25, with reference to pp. electrical properties of amber. The amuletic, magical, or 350–52 in the same catalogue. Benzel cites J. Spacy, “Emblems apotropaic properties of pre-Roman amber objects are noted in Rituals in the Old Babylonian Period,” in Ritual and Sacrifice in by S. Bianco, A. Mastrocinque, A. Russo, and M. Tagliente in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the International Conference Magie d’ambra 2005, passim; Haynes 2000, pp. 45, 100 ; A. Organized by the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 17–20 April 1991, Russo in Treasures 1998, p. 22 ; Bottini 1993, p. 65; Negroni Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 55, ed. J. Quaegebeur (Leuven, Catacchio 1989, p. 659 (and elsewhere); Fuscagni 1982, p. 110; 1993), pp. 411–20; Z. Bahrani, “The Babylonian Visual Image,” Hölbl 1979, vol. 1, pp. 229ff., who (as quoted by Waarsenburg in The Babylonian World, ed. G. Leick (New York and London, 1995) sees “all amulets [as having] had a similar, not exactly 2003), pp. 155–70; and Z. Bahrani, The Graven Image: defined magic power; possibly they served against natural Representation in Babylonia and Assyria (Philadelphia, 2003), p. dangers such as animal bites, or against supranatural dangers 127. See also H. Wildberger, Isaiah 1–12: A Commentary, trans. such as the evil eye”; La Genière 1961; Richter 1940, pp. 86, 88; T. H. Trapp (1991; repr., Minneapolis, 2002). andRE, vol. 3, part 1, esp. cols. 301–3, s.v. “Bernstein” (by Blümner). For the Mycenaean period, see Bouzek 1993, p, 141, 15. Amber itself, and most of the subjects of figured amber, have “who rightly insists first on the quasimagical properties of fertility aspects. Modern Westerners tend to discuss the fertility amber (not just the prestige),” as A. Sherratt notes in “Electric and fecundity beliefs and rites of earlier peoples in the context Gold: Reopening the Amber Route,” Archaeology 69 (1995): of an increase of humans, hunt animals, edible botanics, 200–203, his review of Beck and Bouzek 1993. Compare, agricultural products, and domesticated crops, which limits our however, the more cautious opinion of Hughes-Brock 1985, p. understanding of fertility imagery, both its making and its use. 259: “Most amber is in ordinary bead form; since it is That fertility magic was used to control reproduction (via, e.g., consistently found alongside standard beads of other birth spacing) as well as spur procreation was first brought to materials, we cannot prove that the Mycenaeans thought of it my attention by R. White (public lecture 1999). See White 2003 as having any special amuletic value.” (in n. 2, above), p. 58, where he cites G. H. Luquet, L’art néo- calédonien: Documents recueillis par Marius Archambault (Paris, 10. Eichholz 1962 is the edition used throughout this text. 1926), and P. Ucko and A. Rosenfeld, Paleolithic Cave Art 11. J. Evans, Magical Jewels of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, (London, 1967). Luquet was among the first to raise doubts Particularly in England (Oxford, 1922), p. 13. about the idea that Paleolithic peoples were motivated to increase human fecundity through magical acts. Ucko and 12. The subjects and forms of many pre-Roman figured ambers Rosenfeld were among the first to write that hunters and have precedents thousands of years older. The earliest gatherers are generally more interested in limiting population surviving animal and human subjects in amber from northern growth than in increasing it. Compare the discussion by J. Europe are dated to the eighth millennium; see, for example, Assante, “From Whores to Hierodules,” in Ancient Art and Its M. Iršenas, “Stone Age Figurines from the Baltic Area,” in Historiography, ed. A. A. Donohue and M. D. Fullerton Proceedings of the International Interdisciplinary Conference: (Cambridge, 2003), p. 26, where she contrasts “Yahweh’s Baltic Amber in the Natural Sciences, Archaeology and Applied Art, command to be fruitful and multiply, and the Bible’s emphasis ed. A. Butrimas (Vilnius, 2001), pp. 77–86; M. Ots, “Stone Age on progeny in general,” with the Mesopotamian “gods of Amber Finds in Estonia,” in Beck et al. 2003, pp. 96–107; M. prebiblical flood myths who did not destroy mankind because Irinas, “Elk Figurines in the Stone Age Art of the Baltic Area,” in they sinned but because they overpopulated and made too Prehistoric Art in the Baltic Region, ed. A. Butrimas (Vilnius, much noise.” Assante cites A. Kilmer, “The Mesopotamian 2000), pp. 93–105; and I. Loze, “Prehistoric Amber Ornaments Concept of Overpopulation and Its Solution as Reflected in the in the Baltic Region,” in Baltica 2000, pp. 18–19. An amber duck Mythology,” Orientalia, n.s., 41 (1972): 160–77. found in a Danish Paleolithic context of 6800–4000 B.C. is the 16. D. Frankfurter, Bryn Mawr Classical Review 1995.04.12 (review of earliest example of a pendant type popular in Greece and Italy Kotansky 1994). in the seventh century B.C. and first known in the eighth. (See Amber Magic? 11

17. The literature on gifts and gift giving in the ancient world is 18. Thomassen 1999 (n. 8, above), p. 65. extensive. Although previous ownership of excavated objects is 19. CompareFaraone 1992, p. 37: “There is a tendency for all ordinarily difficult to establish, two Etruscan finds and one protective images, regardless of their ‘original’ purpose or the Etrusco-Campanian find might be seen as exempla of specific crisis that led to their manufacture, to assume a wider presentation, parting, and exchange articulated around and wider role in the protection of a place, until they achieve a banquets. Were these items exchanged among guests/friends? status as some vague ‘all-purpose’ phylactery against any and Were they components of a dowry or bride wealth, ransom or all forms of evil.” prizes, or funerary tributes? Haynes 2000, p. 69, cites the silver vessels deposited circa 660 B.C. with an aristocratic lady in the 20. Seen. 152. Regolini-Galassi Tomb at Cerveteri, inscribed with a male name in the genitive, and suggests that these luxury objects were the 21. The scenario of multiple ritual specialists recorded by the property of her husband. The seventh-century gold fibula, with tenth-century A.D. compiler Ibn al-Nadim, who pronounced its inscription in granulation, from Casteluccio-La Foce (Siena), Egypt “the Babylon of the magicians,” might provide a later in the Louvre (Bj 816), is a gift-ornament that recalls the fibulae model for pragmatic ritual expertise at all levels and the range of the peplos offered to Penelope (Odyssey 18.292–95). For the of activities of itinerant artisans and healers in pre-Roman Italy. Louvre pin, see Cristofani, in Cristofani and Martelli 1983, no. He records, “A person who has seen this state of affairs has 103; and Haynes 2000, p. 6809, fig. 47. The inscription on an told me that there still remain men and women magicians and Etrusco-Campanian bronzelebesfound in Tomb 106 at Braida that all of the exorcists and magicians assert that they have di Vaglio, which belonged to a woman of about sixty (the tomb seals, charms of paper … and other things used for their arts”: also included two amber figured pendants, a satyr’s head and Ibn al-Nadim, Kitāb al-Fihrist, trans. Bayard Dodge, The Fihrist of a Cypriote-type Herakles), is another important example; for al-Nadim: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture (New York, the inscription, see M. Torelli with L. Agostiniani, in Bottini and 1970), p. 726 (quoted in D. Frankfurter, “Ritual Expertise in Setari 2003, p. 63, and appendix I, pp. 113–17. These Roman Egypt and the Problem of the Category ‘Magician,’” in inscriptions are further evidence of networked elites taking Envisioning Magic: A Princeton Seminar and Symposium, ed. P. advantage of their literacy. Schäfer and H. G. Kippenberg [Princeton, 1997], p. 30). 12 INTRODUCTION

What Is Amber? Figure 8 Sources of amber in the ancient world. Map by David Fuller. It is important to say that amber is much studied but still It is clear that the amber is not derived from the not fully understood. The problems begin with the names modern species of Pinus, but there are mixed signals by which the material is known: amber, Baltic amber, from suggestions of either an araucarian Agathis-like fossil resin, succinite, and resinite. Although all these or a pinaceous Pseudolarix-like resin producing terms have been used to describe the material discussed tree.… Although the evidence appears to lean more in this catalogue, they have confused as much as they toward a pinaceous source, an extinct ancestral tree have clarified. It is generally accepted that amber is is probably the only solution.23 derived from resin-bearing trees that once clustered in dense, now extinct forests.22 Despite decades of study, Geologically, amber has been documented throughout the there is no definite conclusion about the botanical source world (figure 8), with most deposits found in Tertiary- of the vast deposits of Baltic amber, as Jean H. period sediments dating to the Eocene, a few to the Langenheim recently summarized in her compendium on Oligocene and Miocene, and fewer still to later in the plant resins: Tertiary. Amber is formed from resin exuded from tree bark (figure 9), although it is also produced in the heartwood. Resin protects trees by blocking gaps in the 13

bark. Once resin covers a gash or break caused by chewing insects, it hardens and forms a seal. Resin’s antiseptic properties protect the tree from disease, and its stickiness can gum up the jaws of gnawing and burrowing insects.24 In the primordial “amber forest,” resin oozed down trunks and branches and formed into blobs, sheets, and stalactites, sometimes dripping onto the forest floor. On some trees, exuded resin flowed over previous flows, creating layers. The sticky substance collected detritus and soil and sometimes entrapped flying and crawling creatures (figure 10). Eventually, after the trees fell, the resin-coated logs were carried by rivers and tides to deltas in coastal regions, where they were buried over time in sedimentary deposits. Most amber did not originate in the place where it was found; often, it was deposited and found at a distance from where the resin-producing trees Figure 10 Damselfly in Dominican amber, L: 4.6 cm (14⁄ in.). Private 5 grew. Most known accumulations of amber are collection. Photo: D. Grimaldi / American Museum of Natural History. redepositions, the result of geological activity.25 Chemically, the resin that became amber originally contained liquids (volatiles) such as oils, acids, and alcohols, including aromatic compounds (terpenes) that produce amber’s distinctive resinous smell.26 Over time, the liquids dissipated and evaporated from the resin, which began to harden as the organic molecules joined to form much larger ones called polymers. Under the right conditions, the hardened resin continued to polymerize and lose volatiles, eventually forming amber, an inert solid that, when completely polymerized, has no volatiles.27 Most important, the resins that became amber were buried in virtually oxygen-free sediments. How long does it take for buried resin to become amber? The amberization process is a continuum extending from freshly hardened resins to rocklike ones, and, as David Grimaldi points out, “No single feature identifies at what age along that continuum the substance becomes amber.”28Langenheim explains: “With increasing age, the maturity of any given resin will increase, but the rate at which it occurs depends on the prevailing geologic conditions as well as the composition of the resin.… Changes appear to be a response primarily to geothermal stress since chemical change in the resin accelerates at higher temperatures.”29 While some experts maintain that only material that is several million years old or older is sufficiently cross- Figure 9 Amber formed on trees. In Tractatus De lapidus, Ortus sanitatis linked and polymerized to be classified as amber, others (Mainz: Jacob Meydenbach, June 23, 1491), sequence 776. Folio: 30.2 x 20.6 cm opt for a date as recent as forty thousand years before the (117⁄ x 81⁄ in.). Handcolored woodcut. Courtesy of the Boston Medical 30 8 8 present. Much depends on the soil conditions of the Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. resin’s burial. In its final form, amber is much more stable than the original substance. Amber is organic, like petrified wood or dinosaur bones, but, unlike those substances, it retains its chemical composition over time, 14 INTRODUCTION

and that is why some experts resist calling it a fossil resin NOTES (a nevertheless useful term).31 Amber can also preserve plant matter (figure 11), bacteria, fungi, worms, snails, 22. Recent sources consulted include E. Trevisani, “Che cosa è insects, spiders, and (more rarely) small vertebrates. l’ambra,” in Magie d’ambra 2005, pp. 14–17; E. Ragazzi, L’ambra, Some pieces of amber contain water droplets and farmaco solare: Gli usi nella medicina del passato (Padua, 2005); bubbles, products of the chemical breakdown of organic Langenheim 2003;Weitshaft and Wichard 2002; Pontin and Celi matter. It is not entirely understood how resins preserve 2000; Poinar and Poinar 1999; Ross 1998; Bernstein 1996; Grimaldi 1996; Å. Dahlström and L. Brost, The Amber Book organic matter, but presumably the chemical features of (Tucson, AZ, 1996); Anderson and Crelling 1995; B. Kosmowska- amber that preserve it over millennia also preserve flora Ceranowicz and T. Konart, Tajemnice bursztynu (Secrets of and fauna inside it.32 It must be that amber’s “amazing Amber)(Warsaw, 1989); Beck and Bouzek 1993; and J. Barfod, F. life-like fidelity of preservation … occurs through rapid Jacobs, and S. Ritzkowski, Bernstein: Schätze in Niedersachsen and thorough fixation and inert dehydration as well as (Seelze, 1989). The late C. W. Beck’s lifetime of work on amber other natural embalming properties of the resin that are analysis is critical to any study of the material. still not understood.”33 The highly complex process that results in amber formation gave rise to a wealth of 23. Langenheim 2003, p. 169. speculation about its nature and origins. Whence came a 24. Ross 1998, p. 2. substance that carried within it the flora and fauna of 25. Nicholson and Shaw 2000, p. 451, with reference to Beck and another place and time, one with traces of the earth and Shennan 1991, pp. 16–17. sea, one that seemed even to hold the light of the sun? 26. Ross 1998, p. 3: “The polymers are cyclic hydrocarbons called terpenes.… Amber generally consists of around 79% carbon, 10% hydrogen, and 11% oxygen, with a trace of sulphur.” 27. Ross 1998, p. 3. 28. Grimaldi 1996, p. 16. 29. Langenheim 2003, pp. 144–45. 30. Langenheim 2003, p. 146, following Anderson and Crelling 1995. 31. Ross 1998, p. 3, in describing the amberization process, points to the critical element of the kinds of sediments in which the resin was deposited: “but what is not so clear is the effect of water and sediment chemistry on the resin.” In the ancient world, amber does not seem to have been considered a fossil like other records of preserved life—petrified wood, skeletal material, and creatures in limestone. See A. Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times (Princeton, 2000). 32. Ross 1998, p. 12. 33. Langenheim 2003, p. 150. Figure 11 Cone in Baltic amber, L: 15.2 cm (6 in.). Private collection. Photo: D. Grimaldi / American Museum of Natural History. What Is Amber? 15

Where Is Amber Found? Deposits of amber occur throughout both the Old and the New Worlds, and many varieties are recognized. Of the many kinds of amber found in the Old World, the most plentiful today, as in antiquity, is Baltic amber (figure 12), or succinite (so called because it has a high concentration of succinic acid). This early Tertiary (Upper Eocene–Lower Oligocene) amber comes mainly from around the shores of the Baltic Sea, from today’s Lithuania, Latvia, Russia (Kaliningrad), Poland, southern Sweden, northern Germany, and Denmark. The richest deposits are on and around the Samland peninsula, a large, fan-shaped area that corresponds to the delta region of a river that once drained an ancient landmass that geologists call Fennoscandia. This ancient continent now lies beneath the Baltic Sea and the surrounding land. Although this area has the largest concentration of amber in the world, it is a secondary deposition. Amazingly, the fossil resin “was apparently eroded from marine sediments near sea level, carried ashore during storms, and subsequently carried by water and glaciers to secondary deposits across Figure 12 Baltic amber, L: 2.2 cm (7⁄8 in.). Private collection. Photograph © much of northern and eastern Europe” over a period of Lee B. Ewing. approximately twenty million years.34 In antiquity, most amber from the Baltic shore was harvested from shallow Other kinds of amber used by ancient Mediterranean waters and beaches where it had washed up (once again, peoples have been identified with sources in today’s Sicily,36 Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan.37 In addition to millennia later), especially during autumn storms that agitated the seabeds. It was only in the early modern northern European sources, ancient accounts mention amber from Liguria, Scythia,38 Syria, India, Ethiopia, and period that amber began to be mined. With the introduction of industrial techniques, huge amounts have Numidia. However, of the varieties used in antiquity and been extracted since the nineteenth century. It is known today, only succinite, or Baltic amber, is found in estimated that up to a million pounds of amber a year was the large, relatively sturdy, jewelry-grade pieces such as dug from the blue earth layer of the Samland peninsula in were used for the sizable objects of antiquity, like the pre- the first decades of the twentieth century.35 Roman pendants of this catalogue, or for the complex carvings, vessels, and containers of Roman date. Small pieces of amber and the wastage of larger compositions could have been used for tiny carvings and other purposes. Non-jewelry-grade amber would also have been employed in inlay, incense and perfume, pharmaceuticals, and varnish, as is still the case in the modern period. Burmite (found in Burma, now Myanmar) and some amber from China, types also found in large, high-grade 16

pieces, have long histories of artistic and other uses in Anthropological Association 1 (1907): 3. On amber from Asia.39 Myanmar, seeLangenheim 2003, p. 279: “Amber was collected from shallow mines in the Nagtoimow Hills in northern Burma NOTES and the major portion was sent to trade centers such as Mandalay and Mogaung … and then brought by traders to 34. Langenheim 2003, p. 164. Yunnan province in China where it was used by Chinese craftsmen from as early as the first Han dynasty (206 B.C. to 35. For the modern mining of Baltic amber, see the overview in A.D. 8).” Langenheim draws from H. L. Chibber, The Mineral Rice 2006, chap. 3. Resources of Burma (London, 1934). See also D. A. Grimaldi, M. 36. On Sicilian amber, see Trevisani in Magie d’ambra 2005, p. 16; S. Engel, and P. C. Nascimbene, “Fossiliferous Cretaceous Schwarzenberg 2002;Grimaldi 1996, p. 42; C. W. Beck and H. Amber from Myanmar (Burma): Its Rediscovery, Biotic Harnett, “Sicilian Amber,” in Beck and Bouzek 1993, pp. 36–47; Diversity, and Paleontological Significance,” Novitates 3361 Strong 1966, pp. 1–2, 4; and Buffum 1900. Pliny and the sources (March 26, 2002): 1–7; V. V. Zherikhin and A. J. Ross, “A Review he consulted, including Theophrastus, discuss amber from of the History, Geology, and Age of Burmese Amber Liguria. Ligurian deposits may indeed have been known in (Burmite),” Geology Bulletin 56, no. 1 (2000): 1–3; V. V. Zherikhin antiquity. Larger deposits may have been exhausted in and A. J. Ross, “The History, Geology, Age and Fauna (Mainly antiquity. The ancient boundaries of Liguria include areas Insects) of Burmese Amber, Myanmar,” in Bulletin of the where non-jewelry-grade amber is known, as Trevisani maps. If Natural History Museum, ed. A. J. Ross (London, 2000); Ross it was dug up rather than originating in an oceanic or riverine 1998, p. 15; Bernstein 1996; Grimaldi 1996, pp. 40–42, 194–208; source, it may not have had the same value. Moreover, the and S. S. Savkevich and T. N. Sokolova, “Amber-like Fossil proximity of the material to its consumption point might have Resins of Asia and the Problems of Their Identification in undermined its value. See n. 110 for more on amber’s value. Archaeological Contexts,” in Beck and Bouzek 1993, pp. 48–50. In the annals of the Han and later dynasties, amber is 37. In addition to the sources listed in n. 36, above, see J. M. Todd, mentioned repeatedly as one of the notable products of “The Continuity of Amber Artifacts in Ancient Palestine: From Roman Syria; see F. Hirth, China and the Roman Orient: the Bronze Age to the Byzantine,” in Beck and Bouzek 1993, pp. Researches into Their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as 236–46, and J. M. Todd, “Baltic Amber in the Ancient Near East: Represented in Old Chinese Records (Shanghai and Hong Kong, A Preliminary Investigation,” Journal of Baltic Studies 16, no. 3 1885), pp. 35–96. (1985): 292–302. On Lebanese amber, see G. O. Poinar, Jr., and Pliny (Natural History 37.11) cites authors who attest to amber R. Milki, Lebanese Amber: The Oldest Insect Ecosystem in Fossilized from Syria and India as well as to other sources east and south Resin (Corvallis, OR, 2001), p. 15, who describe a few fist-sized of Italy. Poinar and Milki, 2001 (n. 37, above), p. 77, suggest pieces of “quite durable” Lebanese amber found in modern that many “nineteenth and twentieth century reports of amber times, although generally Lebanese amber is collected in small, finds in western Syria probably referred to localities within the highly fractured pieces less than a centimeter in diameter. See confines of present-day Lebanon, since the latter had been a also Grimaldi 1996, pp. 35–36. republic within the borders of Syria for a number of years.” For 38. On Scythian amber, see E. H. G. Minns, Greeks and Scythians: A amber from the ancient Near East, see M. Heltzer, “On the Survey of Ancient History and Archaeology on the North Coast of Origin of the Near Eastern Archaeological Amber,” in the Euxine from the Danube to the Caucasus (1913; repr., New Languages and Cultures in Contact, Orientalia Lovaniensia York, 1971), pp. 7, 440, with reference to Pliny, Natural History Analecta 96, ed. K. van Lerberghe and G. Voet (Leuven, 1999), 33.161, 37.33, 37.40, 37.64, 37.65, and 37.119. pp. 169–76; S. M. Chiodi, “L’ambra nei testi mesopotamici,” Protostoria e storia del ‘Venetorum Angulus’: Atti del XX Convegno 39. The geological source of Ming- and Ching-dynasty amber di studi etruschi ed italici, Portogruaro, Quarto d’Altino, Este, Adria, carvings is not assured. The amber might have come from 16–19 ottobre 1996 (Pisa and Rome, 1999); and J. Oppert, Myanmar (Burma) or possibly from European, “Syrian,” or “L’Ambre jaune chez les Assyriens,” Recueil de travaux relatifs à Chinese sources. “China does have some large natural deposits la philologie et à l’archéologie à égyptiennes et assyriennes 21 of amber in Fushun, but these appear not to have been (1880): 331ff. exploited” (Grimaldi 1996, p. 194). See also B. Laufer, “Historical Jottings on Amber in Asia,” Memoirs of the American Where Is Amber Found? 17

The Properties of Amber Amber is a light material, with a specific gravity ranging from 1.04 to 1.10, only slightly heavier than that of water (1.00). Amber may be transparent or cloudy, depending on the presence and number of air bubbles (figure 13). It frequently contains large numbers of microscopic air bubbles, allowing it to float and to be easily carried by rivers or the sea. White opaque Baltic amber may contain as many as 900,000 minuscule air bubbles per square millimeter and floats in fresh water. Clear Baltic amber sinks in fresh water but is buoyant in saltwater. Baltic amber has some distinguishing characteristics rarely found in other types of amber: it commonly contains tiny hairs that probably came from the male flowers of oak trees, and tiny pyrite crystals often fill cracks and inclusions. Another feature found in Baltic amber is the white coating partly surrounding some insect inclusions, formed from liquids that escaped from the decaying insects.40 Figure 13 Extinct termite, Mastotermes electrodominicus, in Dominican amber, L: 4.6 cm (14⁄5 in.). Photo: D. Grimaldi / American Museum of Natural History. Amber’s hardness varies from 2 to 3 on the Mohs scale (talc is 1 and diamond 10). This relative softness means that amber is easily worked. It has a melting-point range of 200 to 380°C, but it tends to burn rather than melt. Amber is amorphous in structure and, if broken, can produce a conchoidal, or shell-like, fracture. It is a poor conductor and thus feels warm to the touch in the cold, and cool in the heat. When friction is applied, amber becomes negatively charged and attracts lightweight 18

particles such as pieces of straw, fluff, or dried leaves. Its clear yellow to clear orange or red to opaque yellows, ability to produce static electricity has fascinated oranges, reds, and tans. Inclusions are common. observers from the earliest times. Amber’s magnetic property gave rise to the word electricity: amber (Greek, elektron) was used in the earliest experiments on electricity.41 Amber’s natural properties inspired myth and legend and dictated its usage. In antiquity, before the development of colorless clear glass that relies on a complex technique perfected in the Hellenistic period, the known clear materials were natural ones: water and some other liquids; ice; boiled honey and some oils; rock crystal; some precious stones; and amber.42Transparent amber is a natural magnifier, and, when formed into a regularly curved surface and given a high polish, it can act as a lens.43 A clear piece of Figure 14 Two typical pieces of Baltic amber. Pale yellow amber was amber with a convex surface can concentrate the sun’s preferred by the ancient Greeks and Etruscans. Opaque orange amber was rays. One ancient source suggests that such polished especially fashionable in Imperial Rome. L (orange amber): 9 cm (31⁄2 in.). L ambers were used as burning lenses. (yellow amber): 5 cm (2 in.). Private collection. Photograph © Lee B. Ewing. Once amber is cleaned of its outer layers and exposed to air, its appearance—its color, degree of transparency, and surface texture—eventually will change. As a result of the action of oxygen upon the organic material, amber will darken: a clear piece will become yellow; a honey-colored piece will become red, orange-red, or red-brown, and the surface progressively will become more opaque (figure 14).44 Oxidation commences quite quickly and starts at the surface, which is why some amber may appear opaque or dark on its surface and translucent at breaks or when subjected to transmitted light. However, the progress of oxidation is variable and depends on the time of exposure and other factors, such as the amount and duration of exposure to light. In archaeologically Figure 15 Female Head Pendants, from Tomb 740 B, Valle Pega, Spina, a recovered amber, the state of the material is dependent tomb dating to the end of the 5th century B.C. Amber, H: 4.8 cm (17⁄8 in.), W: upon burial conditions, and the degree of oxidation can 2.8 cm (11⁄8 in.), D: 1.2 cm (1⁄2 in.) and H: 4.5 cm (13⁄4 in.), W: 2.8 cm (11⁄8 in.), D: vary widely, as the Getty collection reveals. The 1.4 cm (1⁄2 in.). Ferrara, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, 44877 and 44878. breakdown of the cortex causes cracking, fissuring, Ferrara, Museo Archeologico Nazionale / IKONA. flaking, chipping, and, eventually, fractures. Only a very few ancient pieces retain something of their original appearance, in each case because of the oxygen-free environment in which it was buried. For instance, two fifth-century B.C. female head pendants that were excavated at waterlogged Spina are remarkable for their clear, pale yellow color (figure 15).45 A large group of seventh-century B.C. amber-embellished objects from the cemeteries of Podere Lippi and Moroni-Semprini in Verucchio (Romagna) were preserved along with other perishable objects by the stable anaerobic conditions of the Verucchio tombs, which had been sealed with a mixture of water and clay (figure 16).46 Various colors Figure 16 Earrings, from Tomb 23, Podere Lippi, Verucchio. First half of the and degrees of transparency are in evidence, from pale, 7th century B.C. Amber and gold, Diam. (amber, max): 6 cm (23⁄8 in.). Verucchio, Museo Civico Archeologico, 8410-850. Verucchio, Museo Civico Archeologico / IKONA. Properties of Amber 19