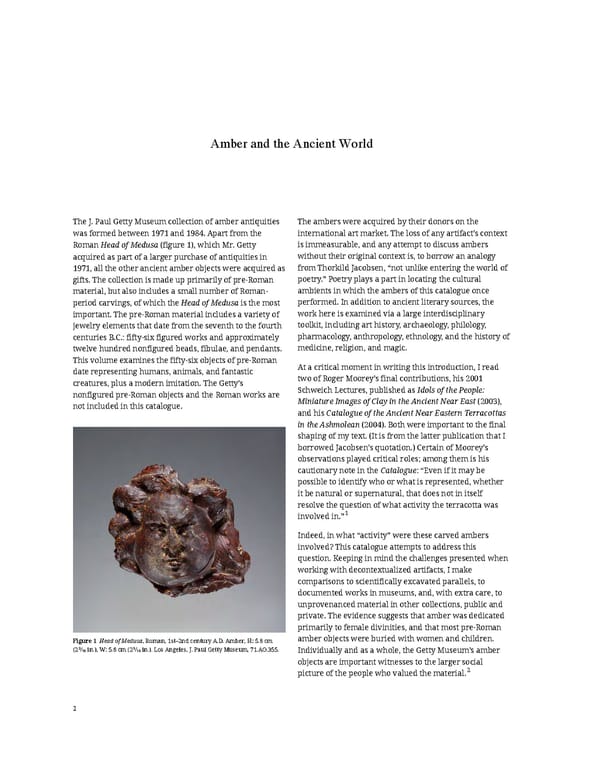

Amber and the Ancient World The J. Paul Getty Museum collection of amber antiquities The ambers were acquired by their donors on the was formed between 1971 and 1984. Apart from the international art market. The loss of any artifact’s context RomanHead of Medusa(figure 1), which Mr. Getty is immeasurable, and any attempt to discuss ambers acquired as part of a larger purchase of antiquities in without their original context is, to borrow an analogy 1971, all the other ancient amber objects were acquired as from Thorkild Jacobsen, “not unlike entering the world of gifts. The collection is made up primarily of pre-Roman poetry.” Poetry plays a part in locating the cultural material, but also includes a small number of Roman- ambients in which the ambers of this catalogue once period carvings, of which the Head of Medusa is the most performed. In addition to ancient literary sources, the important. The pre-Roman material includes a variety of work here is examined via a large interdisciplinary jewelry elements that date from the seventh to the fourth toolkit, including art history, archaeology, philology, centuries B.C.: fifty-six figured works and approximately pharmacology, anthropology, ethnology, and the history of twelve hundred nonfigured beads, fibulae, and pendants. medicine, religion, and magic. This volume examines the fifty-six objects of pre-Roman At a critical moment in writing this introduction, I read date representing humans, animals, and fantastic two of Roger Moorey’s final contributions, his 2001 creatures, plus a modern imitation. The Getty’s Schweich Lectures, published as Idols of the People: nonfigured pre-Roman objects and the Roman works are Miniature Images of Clay in the Ancient Near East (2003), not included in this catalogue. and his Catalogue of the Ancient Near Eastern Terracottas in the Ashmolean (2004). Both were important to the final shaping of my text. (It is from the latter publication that I borrowed Jacobsen’s quotation.) Certain of Moorey’s observations played critical roles; among them is his cautionary note in the Catalogue: “Even if it may be possible to identify who or what is represented, whether it be natural or supernatural, that does not in itself resolve the question of what activity the terracotta was involved in.”1 Indeed, in what “activity” were these carved ambers involved? This catalogue attempts to address this question. Keeping in mind the challenges presented when working with decontextualized artifacts, I make comparisons to scientifically excavated parallels, to documented works in museums, and, with extra care, to unprovenanced material in other collections, public and private. The evidence suggests that amber was dedicated primarily to female divinities, and that most pre-Roman Figure 1 Head of Medusa, Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D. Amber, H: 5.8 cm amber objects were buried with women and children. (23⁄10 in.), W: 5.8 cm (23⁄10 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 71.AO.355. Individually and as a whole, the Getty Museum’s amber objects are important witnesses to the larger social picture of the people who valued the material.2 2

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Page 11 Page 13

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Page 11 Page 13