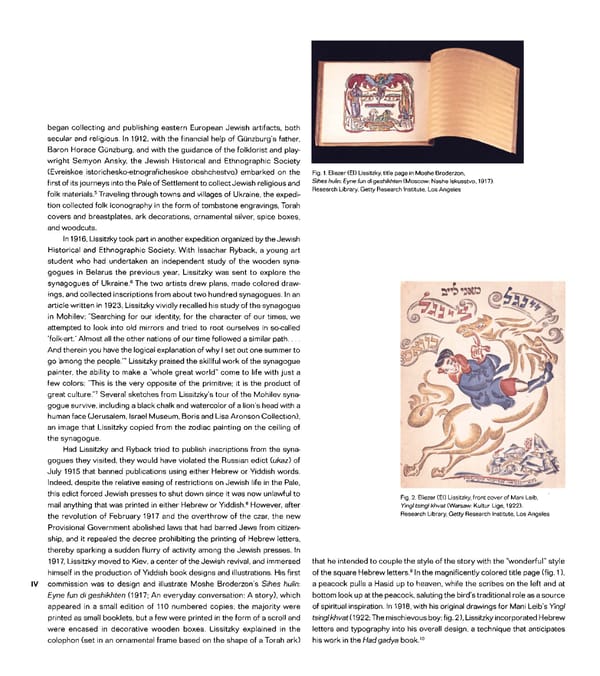

began collecting and publishing eastern European Jewish artifacts, both secular and religious. In 1912, with the financial help of Gunzburg's father, Baron Horace Gunzburg, and with the guidance of the folklorist and play wright Semyon Ansky, the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society (Evreiskoe istoricheskoetnograficheskoe obshchestvo) embarked on the Fig. 1. Eliezer (El) Lissitzky, title page in Moshe Broderzon, first of its journeys into the Pale of Settlement to collect Jewish religious and Sihes hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (Moscow: Nashe Iskusstvo, 1917). 5 Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles folk materials. Traveling through towns and villages of Ukraine, the expedi tion collected folk iconography in the form of tombstone engravings, Torah covers and breastplates, ark decorations, ornamental silver, spice boxes, and woodcuts. In 1916, Lissitzky took part in another expedition organized by the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society. With Issachar Ryback, a young art student who had undertaken an independent study of the wooden syna gogues in Belarus the previous year, Lissitzky was sent to explore the synagogues of Ukraine.6 The two artists drew plans, made colored draw ings, and collected inscriptions from about two hundred synagogues. In an article written in 1923, Lissitzky vividly recalled his study of the synagogue in Mohilev: "Searching for our identity, for the character of our times, we attempted to look into old mirrors and tried to root ourselves in socalled 'folkart.' Almost all the other nations of our time followed a similar path.... And therein you have the logical explanation of why I set out one summer to go among the people.'" Lissitzky praised the skillful work of the synagogue painter, the ability to make a "whole great world" come to life with just a few colors: "This is the very opposite of the primitive; it is the product of 7 great culture." Several sketches from Lissitzky's tour of the Mohilev syna gogue survive, including a black chalk and watercolor of a lion's head with a human face (Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Boris and Lisa Aronson Collection), an image that Lissitzky copied from the zodiac painting on the ceiling of the synagogue. Had Lissitzky and Ryback tried to publish inscriptions from the syna gogues they visited, they would have violated the Russian edict (ukaz) of July 1915 that banned publications using either Hebrew or Yiddish words. Indeed, despite the relative easing of restrictions on Jewish life in the Pale, this edict forced Jewish presses to shut down since it was now unlawful to Fig. 2. Eliezer (El) Lissitzky, front cover of Mani Leib, 8 mail anything that was printed in either Hebrew or Yiddish. However, after Yingl tsingl khvat (Warsaw: Kultur Lige, 1922). the revolution of February 1917 and the overthrow of the czar, the new Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Provisional Government abolished laws that had barred Jews from citizen ship, and it repealed the decree prohibiting the printing of Hebrew letters, thereby sparking a sudden flurry of activity among the Jewish presses. In 1917, Lissitzky moved to Kiev, a center of the Jewish revival, and immersed that he intended to couple the style of the story with the "wonderful" style himself in the production of Yiddish book designs and illustrations. His first 9 of the square Hebrew letters. In the magnificently colored title page (fig. 1), IV commission was to design and illustrate Moshe Broderzon's Sihes hulin: a peacock pulls a Hasid up to heaven, while the scribes on the left and at Eyne fun di geshikhten (1917; An everyday conversation: A story), which bottom look up at the peacock, saluting the bird's traditional role as a source appeared in a small edition of 110 numbered copies; the majority were of spiritual inspiration. In 1918, with his original drawings for Mani Leib's Yingl printed as small booklets, but a few were printed in the form of a scroll and tsingl khvat C\ 922; The mischievous boy; fig. 2), Lissitzky incorporated Hebrew were encased in decorative wooden boxes. Lissitzky explained in the letters and typography into his overall design, a technique that anticipates colophon (set in an ornamental frame based on the shape of a Torah ark) 10 his work in the Had gadya book.

Had Gadya The Only Kid: Lissitzky 1919 Page 5 Page 7

Had Gadya The Only Kid: Lissitzky 1919 Page 5 Page 7