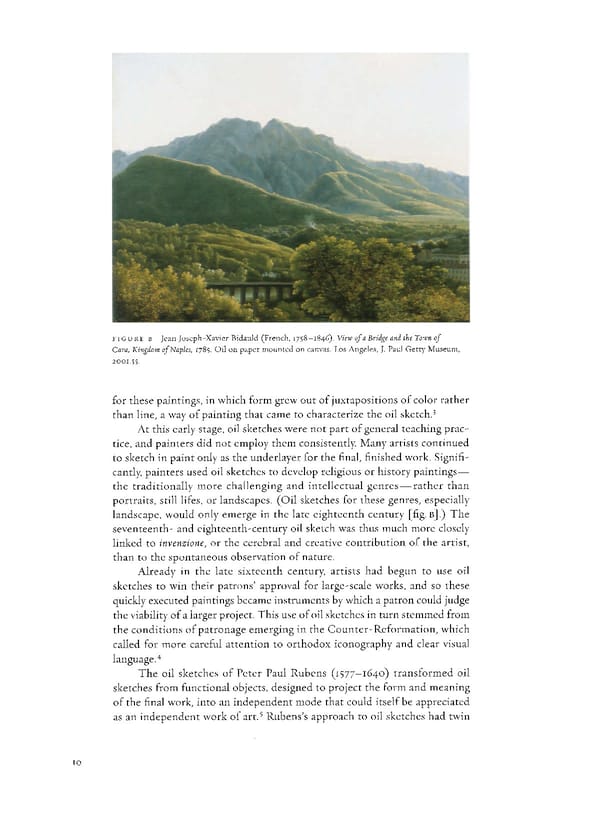

FI GURE B Jean Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (French, 1758 -1846). View of a Bridge and the Town of Cava, Kingdom of Naples, 178$. Oil on paper mounted on canvas. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.55. for these paintings, in which form grew out of juxtapositions of color rather than line, a way of painting that came to characterize the oil sketch.3 At this early stage, oil sketches were not part of general teaching prac- tice, and painters did not employ them consistently Many artists continued to sketch in paint only as the underlayer for the final, finished work. Signifi- cantly painters used oil sketches to develop religious or history paintings— the traditionally more challenging and intellectual genres — rather than portraits, still lifes, or landscapes. (Oil sketches for these genres, especially landscape, would only emerge in the late eighteenth century [fig. B].) The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century oil sketch was thus much more closely linked to invenzione, or the cerebral and creative contribution of the artist, than to the spontaneous observation of nature. Already in the late sixteenth century artists had begun to use oil sketches to win their patrons' approval for large-scale works, and so these quickly executed paintings became instruments by which a patron could judge the viability of a larger project. This use of oil sketches in turn stemmed from the conditions of patronage emerging in the Counter-Reformation, which called for more careful attention to orthodox iconography and clear visual language.4 The oil sketches of Peter Paul Rubens (1577—1640) transformed oil sketches from functional objects, designed to project the form and meaning of the final work, into an independent mode that could itself be appreciated 5 as an independent work of art. Rubens's approach to oil sketches had twin 10

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 10 Page 12

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 10 Page 12