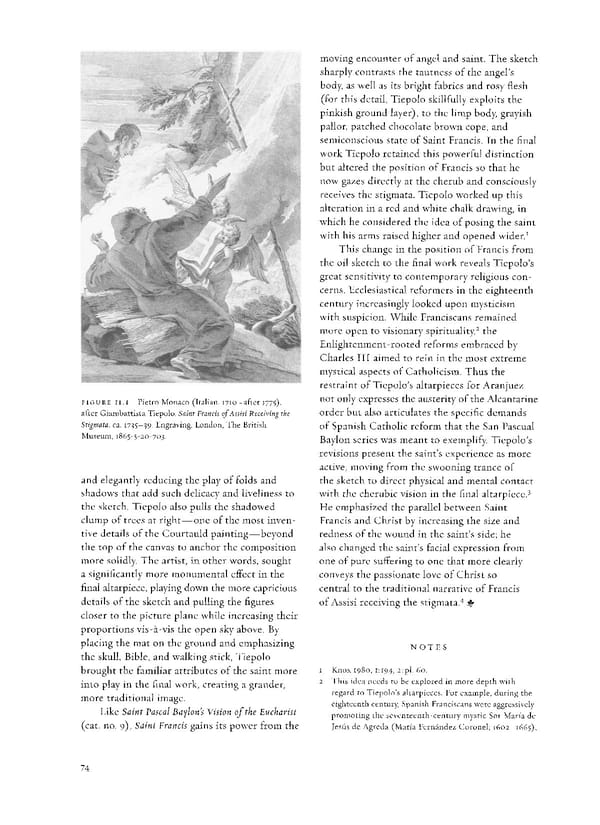

moving encounter of angel and saint. The sketch sharply contrasts the tautness of the angel's body, as well as its bright fabrics and rosy flesh (for this detail, Tiepolo skillfully exploits the pinkish ground layer), to the limp body, grayish pallor, patched chocolate brown cope, and semiconscious state of Saint Francis. In the final work Tiepolo retained this powerful distinction but altered the position of Francis so that he now gazes directly at the cherub and consciously receives the stigmata. Tiepolo worked up this alteration in a red and white chalk drawing, in which he considered the idea of posing the saint 1 with his arms raised higher and opened wider. This change in the position of Francis from the oil sketch to the final work reveals Tiepolo's great sensitivity to contemporary religious con- cerns. Ecclesiastical reformers in the eighteenth century increasingly looked upon mysticism with suspicion. While Franciscans remained more open to visionary spirituality2 the Enlightenment-rooted reforms embraced by Charles III aimed to rein in the most extreme mystical aspects of Catholicism. Thus the restraint of Tiepolo's altarpieces for Aranjuez FIGURE II.I Pietro Monaco (Italian, 1710-after 1775), not only expresses the austerity of the Alcantarine after Giambattista Tiepolo. Saint Francis of Assist Receiving the order but also articulates the specific demands Stigmata, ca. 1735-39. Engraving. London, The British of Spanish Catholic reform that the San Pascual Museum, 1865-5-20-703. Baylon series was meant to exemplify. Tiepolo's revisions present the saint's experience as more active, moving from the swooning trance of and elegantly reducing the play of folds and the sketch to direct physical and mental contact shadows that add such delicacy and liveliness to 3 with the cherubic vision in the final altarpiece. the sketch. Tiepolo also pulls the shadowed He emphasized the parallel between Saint clump of trees at right—one of the most inven- Francis and Christ by increasing the size and tive details of the Courtauld painting—beyond redness of the wound in the saint's side; he the top of the canvas to anchor the composition also changed the saint's facial expression from more solidly. The artist, in other words, sought one of pure suffering to one that more clearly a significantly more monumental effect in the conveys the passionate love of Christ so final altarpiece, playing down the more capricious central to the traditional narrative of Francis details of the sketch and pulling the figures 4 of Assisi receiving the stigmata. & closer to the picture plane while increasing their proportions vis-a-vis the open sky above. By placing the mat on the ground and emphasizing NOTES the skull, Bible, and walking stick, Tiepolo brought the familiar attributes of the saint more 1 Knox 1980, 1:194, 2:pi. 60. into play in the final work, creating a grander, 2 This idea needs to be explored in more depth with more traditional image. regard to Tiepolo's altarpieces. For example, during the Like Saint Pascal Baylon's Vision of the Eucharist eighteenth century, Spanish Franciscans were aggressively promoting the seventeenth-century mystic Sor Maria de (cat. no. 9), Saint Francis gains its power from the Jesus de Agreda (Maria Fernandez Coronel; 1602-1665), 74

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 74 Page 76

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 74 Page 76