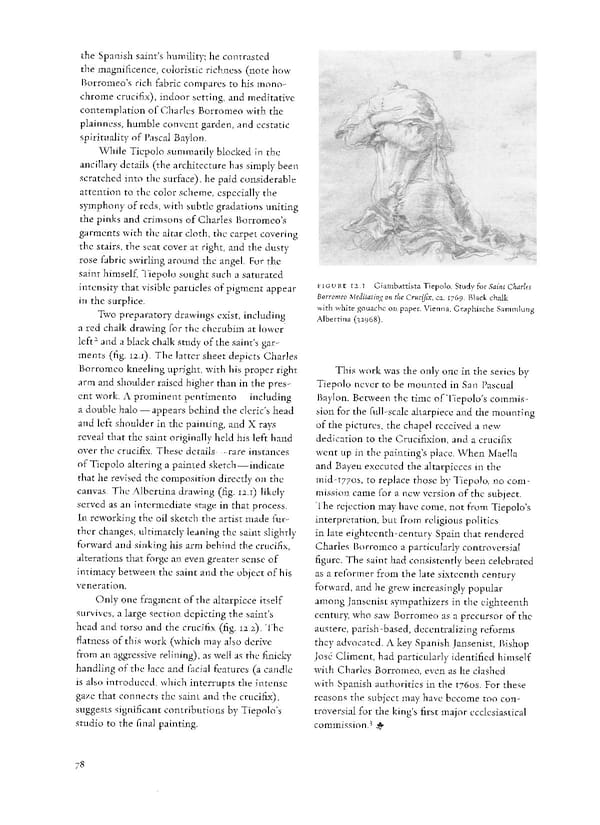

the Spanish saint's humility; he contrasted the magnificence, coloristic richness (note how Borromeo's rich fabric compares to his mono- chrome crucifix), indoor setting, and meditative contemplation of Charles Borromeo with the plainness, humble convent garden, and ecstatic spirituality of Pascal Baylon. While Tiepolo summarily blocked in the ancillary details (the architecture has simply been scratched into the surface), he paid considerable attention to the color scheme, especially the symphony of reds, with subtle gradations uniting the pinks and crimsons of Charles Borromeo's garments with the altar cloth, the carpet covering the stairs, the seat cover at right, and the dusty rose fabric swirling around the angel. For the saint himself, Tiepolo sought such a saturated intensity that visible particles of pigment appear FIGURE 12.1 Giambattista Tiepolo. Study for Saint Charles in the surplice. Borromeo Meditating on the Crucifix, ca. 1769. Black chalk Two preparatory drawings exist, including with white gouache on paper. Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina (32968). a red chalk drawing for the cherubim at lower 2 left and a black chalk study of the saint's gar- ments (fig. 12.i). The latter sheet depicts Charles Borromeo kneeling upright, with his proper right This work was the only one in the series by arm and shoulder raised higher than in the pres- Tiepolo never to be mounted in San Pascual ent work. A prominent pentimento—including Baylon. Between the time of Tiepolo's commis- a double halo — appears behind the cleric's head sion for the full-scale altarpiece and the mounting and left shoulder in the painting, and X rays of the pictures, the chapel received a new reveal that the saint originally held his left hand dedication to the Crucifixion, and a crucifix over the crucifix. These details—rare instances went up in the painting's place. When Maella of Tiepolo altering a painted sketch—indicate and Bayeu executed the altarpieces in the that he revised the composition directly on the mid-i77os, to replace those by Tiepolo, no com- canvas. The Albertina drawing (fig. 12.1) likely mission came for a new version of the subject. served as an intermediate stage in that process. The rejection may have come, not from Tiepolo's In reworking the oil sketch the artist made fur- interpretation, but from religious politics ther changes, ultimately leaning the saint slightly in late eighteenth-century Spain that rendered forward and sinking his arm behind the crucifix, Charles Borromeo a particularly controversial alterations that forge an even greater sense of figure. The saint had consistently been celebrated intimacy between the saint and the object of his as a reformer from the late sixteenth century veneration. forward, and he grew increasingly popular Only one fragment of the altarpiece itself among Jansenist sympathizers in the eighteenth survives, a large section depicting the saint's century, who saw Borromeo as a precursor of the head and torso and the crucifix (fig. 12.2). The austere, parish-based, decentralizing reforms flatness of this work (which may also derive they advocated. A key Spanish Jansenist, Bishop from an aggressive relining), as well as the finicky Jose Climent, had particularly identified himself handling of the lace and facial features (a candle with Charles Borromeo, even as he clashed is also introduced, which interrupts the intense with Spanish authorities in the 17605. For these gaze that connects the saint and the crucifix), reasons the subject may have become too con- suggests significant contributions by Tiepolo's troversial for the king's first major ecclesiastical studio to the final painting. commission.3 78

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 78 Page 80

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 78 Page 80