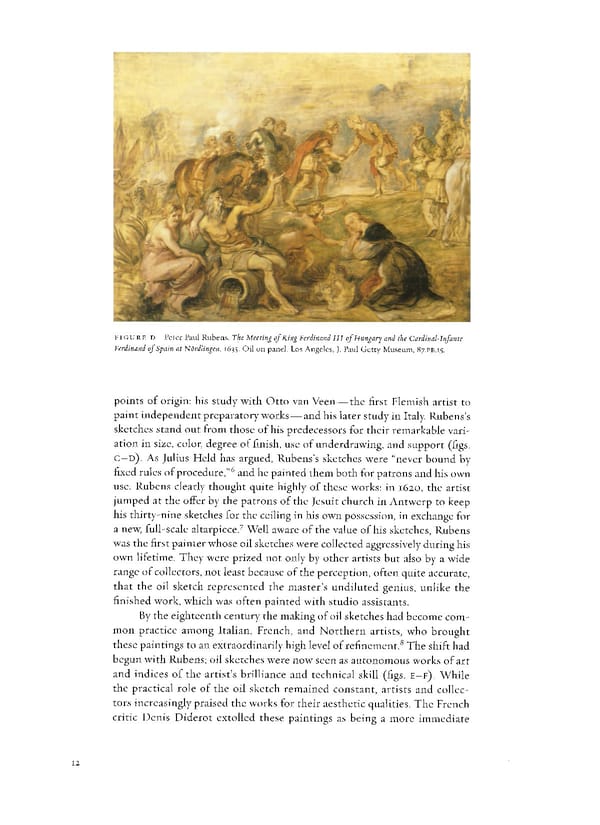

FIGURE D Pete? Paul Rubens. The Meeting of King Ferdinand III of Hungary and the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain at Nordlingen, 1635. Oil on panel. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 87.PB.i5. points of origin: his study with Otto van Veen—the first Flemish artist to paint independent preparatory works — and his later study in Italy. Rubens's sketches stand out from those of his predecessors for their remarkable vari- ation in size, color, degree of finish, use of underdrawing, and support (figs. C-D). As Julius Held has argued, Rubens's sketches were "never bound by 6 fixed rules of procedure/' and he painted them both for patrons and his own use. Rubens clearly thought quite highly of these works: in 1620, the artist jumped at the offer by the patrons of the Jesuit church in Antwerp to keep his thirty-nine sketches for the ceiling in his own possession, in exchange for 7 a new, full-scale altarpiece. Well aware of the value of his sketches, Rubens was the first painter whose oil sketches were collected aggressively during his own lifetime. They were prized not only by other artists but also by a wide range of collectors, not least because of the perception, often quite accurate, that the oil sketch represented the master's undiluted genius, unlike the finished work, which was often painted with studio assistants. By the eighteenth century the making of oil sketches had become com- mon practice among Italian, French, and Northern artists, who brought 8 these paintings to an extraordinarily high level of refinement. The shift had begun with Rubens; oil sketches were now seen as autonomous works of art and indices of the artist's brilliance and technical skill (figs. E-F). While the practical role of the oil sketch remained constant, artists and collec- tors increasingly praised the works for their aesthetic qualities. The French critic Denis Diderot extolled these paintings as being a more immediate 12

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 12 Page 14

Giambattista Tiepolo: Fifteen Oil Sketches Page 12 Page 14