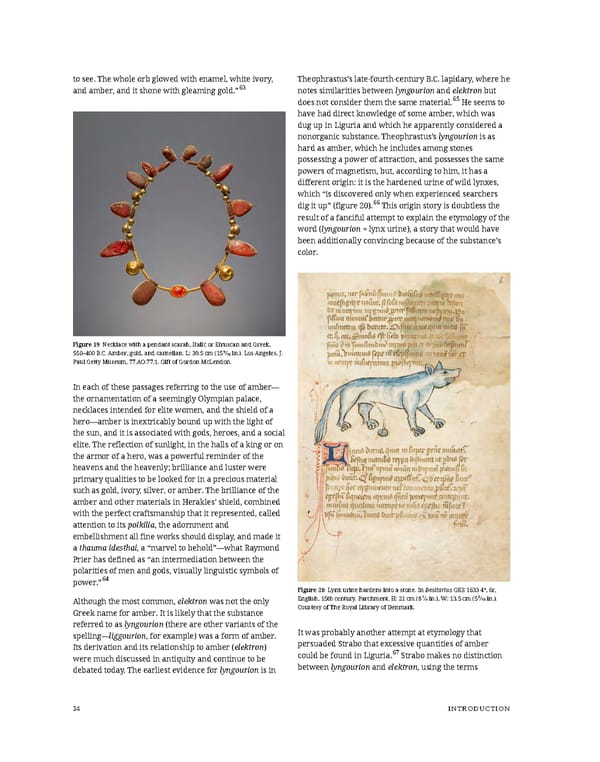

to see. The whole orb glowed with enamel, white ivory, Theophrastus’s late-fourth-century B.C. lapidary, where he and amber, and it shone with gleaming gold.”63 notes similarities between lyngourion and elektron but does not consider them the same material.65 He seems to have had direct knowledge of some amber, which was dug up in Liguria and which he apparently considered a nonorganic substance. Theophrastus’s lyngourion is as hard as amber, which he includes among stones possessing a power of attraction, and possesses the same powers of magnetism, but, according to him, it has a different origin: it is the hardened urine of wild lynxes, which “is discovered only when experienced searchers dig it up” (figure 20).66 This origin story is doubtless the result of a fanciful attempt to explain the etymology of the word (lyngourion = lynx urine), a story that would have been additionally convincing because of the substance’s color. Figure 19 Necklace with a pendant scarab, Italic or Etruscan and Greek, 550–400 B.C. Amber, gold, and carnelian. L: 39.5 cm (159⁄16 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 77.AO.77.1. Gift of Gordon McLendon. In each of these passages referring to the use of amber— the ornamentation of a seemingly Olympian palace, necklaces intended for elite women, and the shield of a hero—amber is inextricably bound up with the light of the sun, and it is associated with gods, heroes, and a social elite. The reflection of sunlight, in the halls of a king or on the armor of a hero, was a powerful reminder of the heavens and the heavenly; brilliance and luster were primary qualities to be looked for in a precious material such as gold, ivory, silver, or amber. The brilliance of the amber and other materials in Herakles’ shield, combined with the perfect craftsmanship that it represented, called attention to its poikilia, the adornment and embellishment all fine works should display, and made it athauma idesthai, a “marvel to behold”—what Raymond Prier has defined as “an intermediation between the polarities of men and gods, visually linguistic symbols of power.”64 Figure 20 Lynx urine hardens into a stone. In Bestiarius GKS 1633 4º, 6r, Although the most common, elektron was not the only English, 15th century. Parchment, H: 21 cm (81⁄4 in.), W: 13.5 cm (53⁄10 in.). Greek name for amber. It is likely that the substance Courtesy of The Royal Library of Denmark. referred to as lyngourion (there are other variants of the spelling—liggourion, for example) was a form of amber. It was probably another attempt at etymology that Its derivation and its relationship to amber (elektron) persuaded Strabo that excessive quantities of amber were much discussed in antiquity and continue to be could be found in Liguria.67 Strabo makes no distinction debated today. The earliest evidence for lyngourion is in betweenlyngourionandelektron, using the terms 24 INTRODUCTION

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Page 33 Page 35

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Page 33 Page 35