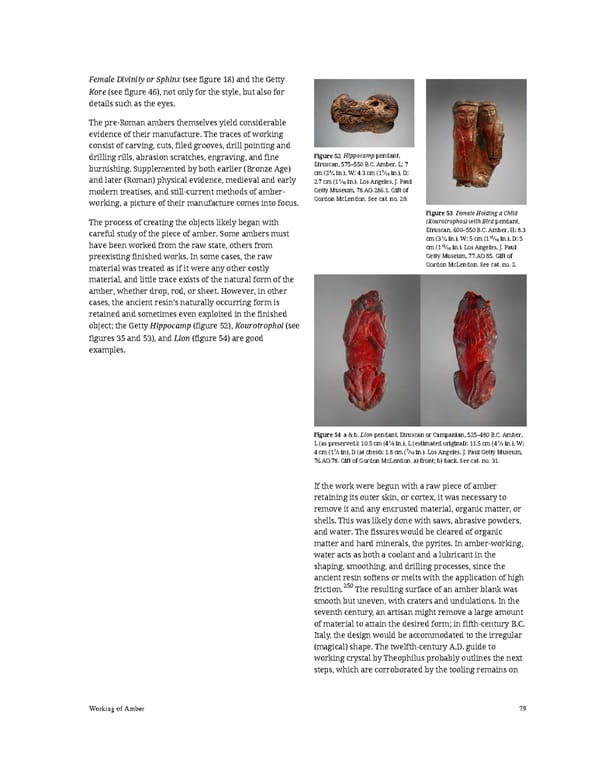

Female Divinity or Sphinx (see figure 18) and the Getty Kore(seefigure 46), not only for the style, but also for details such as the eyes. The pre-Roman ambers themselves yield considerable evidence of their manufacture. The traces of working consist of carving, cuts, filed grooves, drill pointing and drilling rills, abrasion scratches, engraving, and fine Figure 52 Hippocamppendant, burnishing. Supplemented by both earlier (Bronze Age) Etruscan, 575–550 B.C. Amber, L: 7 cm (23⁄4 in.), W: 4.3 cm (17⁄10 in.), D: and later (Roman) physical evidence, medieval and early 2.7 cm (11⁄10 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul modern treatises, and still-current methods of amber- Getty Museum, 78.AO.286.1. Gift of working, a picture of their manufacture comes into focus. Gordon McLendon. Seecat. no. 29. Figure 53 Female Holding a Child The process of creating the objects likely began with (Kourotrophos) with Bird pendant, careful study of the piece of amber. Some ambers must Etruscan, 600–550 B.C. Amber, H: 8.3 cm (31⁄4 in.), W: 5 cm (115⁄16 in.), D: 5 have been worked from the raw state, others from cm (115⁄16 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul preexisting finished works. In some cases, the raw Getty Museum, 77.AO.85. Gift of material was treated as if it were any other costly Gordon McLendon. Seecat. no. 2. material, and little trace exists of the natural form of the amber, whether drop, rod, or sheet. However, in other cases, the ancient resin’s naturally occurring form is retained and sometimes even exploited in the finished object; the Getty Hippocamp (figure 52), Kourotrophoi (see figures 35 and 53), and Lion (figure 54) are good examples. Figure 54 a & b. Lion pendant, Etruscan or Campanian, 525–480 B.C. Amber, L (as preserved): 10.5 cm (41⁄8 in.), L (estimated original): 11.5 cm (41⁄2 in.), W: 4 cm (11⁄2 in), D (at chest): 1.8 cm (7⁄10 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 76.AO.78. Gift of Gordon McLendon. a) front; b) back. See cat. no. 31. If the work were begun with a raw piece of amber retaining its outer skin, or cortex, it was necessary to remove it and any encrusted material, organic matter, or shells. This was likely done with saws, abrasive powders, and water. The fissures would be cleared of organic matter and hard minerals, the pyrites. In amber-working, water acts as both a coolant and a lubricant in the shaping, smoothing, and drilling processes, since the ancient resin softens or melts with the application of high friction.250 The resulting surface of an amber blank was smooth but uneven, with craters and undulations. In the seventh century, an artisan might remove a large amount of material to attain the desired form; in fifth-century B.C. Italy, the design would be accommodated to the irregular (magical) shape. The twelfth-century A.D. guide to working crystal by Theophilus probably outlines the next steps, which are corroborated by the tooling remains on Working of Amber 79

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Page 88 Page 90

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Page 88 Page 90